Bang!. Zwoop. Bada-dap-bap. #

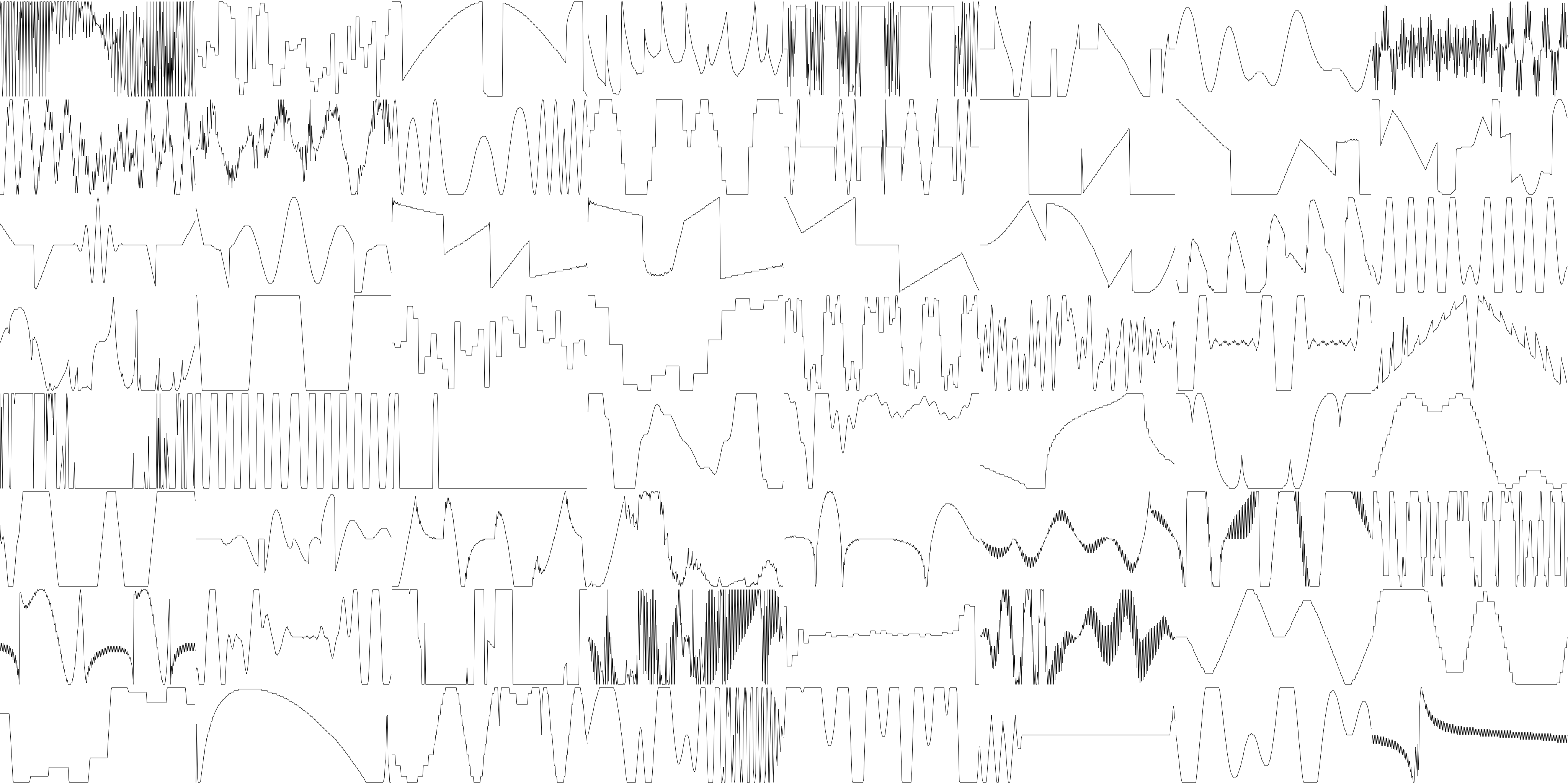

Here’s a sine wave.

I want you to try something. Put your foot back up on your heel and each time you see a new peak, tap the ground. Play a non existent kick drum to each new peak. (or just tap a finger on your desk)

To some people, keeping this beat is difficult. To some it will come naturally. Either is fine. This could be the tempo of a song, the metronome that everything is playing in time to, and it’s just a wave.

But what if we wanted to hear this wave? Well, this wave is (roughly) 1.2Hz. So, you should see a new peak just over once a second. Our ears start to be able to hear things around about 20Hz (20 peaks a second) and can hear up to (if you’ve kept good care of your ears and are lucky) about 20kHz (20,000 peaks a second).

But, wait, I just had you make a sound based on the above wave, and obviously you could hear that. (“No shit” I hear you say.)

In music, we generally want to think of frequency is three ways:

- The frequency of events. Such as the tempo of the song.

- The fundamental frequency of a note.

- The frequency content of a sound.

For the above wave, when used as a metronome for your non-existent kick drum you were doing (1.) but when you just thought about hearing the wave you were doing (2.) So, what’s up with 3?.

Well, to gloss over the quite beautiful math and science, we can think of any wave we’re shown as having a different flavor.

At the absolute most boring center of our umpteen-dimension flavor chart (sweet, savory, spicy - it’s not just “flavor”) everything comes back to the sine wave like above. It’s the most basic. This is because if we look at any of the other waves we can always break them apart into combinations of sine waves at different frequencies and volumes. This is (3) and in musical contexts it’s a large portion of what is called the “timbre” of an instrument.

But, wait, if everything is just a combination of sine waves, what’s this “fundamental” business? The “fundamental” is just the lowest frequency in the wave. But this is really important, because that lowest frequency is (usually) what you’re ear will pick up on and associate as the note being played. This is why we can play the same note on a variety of instruments, recognize them as the same note, and yet they still sound different.

Of course, when we listen to music, we don’t just listen to one wave making a neat tone, we want our wave to be able to change shape over time.

Bang! #

The most fundamental way we can change a sound over time is to change it’s volume. If you clap, the sound may reverberate around the room a bit, sure, but mostly that sound is going to decay very quickly. The same is true of most drum noises.

If you pluck a string on a guitar it will vibrate for a while (unless you intentionally stop it or play another note on the same string) but it will still fade.

Of course, this isn’t our only option. We can also change the frequency content of the wave itself.

Zwoop #

We know our waves have different flavors, and that these flavors can even change over time. But sometimes two flavors can really clash but it be hard to know exactly why. Sure, we can view the waveforms like we’ve been doing above, but wouldn’t it be great if we could have something tell us how spicy our sounds really are?

Well, you can! Introducing the flavometer Spectrum Analyzer. In this picture, our input is the pink wave on the left, and the spectrum analyzer, showing us just how spicy it is and how is on the right (the green graph)

The spectrum analyzer lets you dive in and see (3.) The frequency content of a sound. So, how do you read this thing? The vertical axis is how much of a frequency there is and the horizontal axis is what frequency you’re looking at in the range of human hearing. Note though, this plot is logarithmic. See how the scale isn’t a perfect grid? That’s what I’m talking about. You’ll see that the bottom scale goes from 0 to 100 with a big gap, then from 100 to 1000 the lines start to get closer and closer together until at 1000 this repeats until 10,000. This may seem weird, but it’s for two reasons.

First, and probably more importantly, the way we perceive pitch is actually logarithmic. No, stop, don’t run away! It’s not that complicated.

Both of these notes are A. The keyboard repeats itself. But we know the blue one is higher pitch than the red one. The only difference is which octave the key is played at. I’ll get more into music theory and the division of notes on the keyboard later, but what you should know for now is that when we go up an octave, it’s a perfect doubling in frequency (similarly, down an octave means half the frequency).

The reason this matters to us for the moment is because as a natural consequence of this notes low down on the keyboard will be close together in frequency, while notes high up will be far apart.

For example, an A1 is 55Hz and a A#1 is 58.27Hz, so only 3.27Hz difference, but A6 is 1760Hz and a A#6 is 1864.66Hz, so 104.66Hz difference.

This means that by squishing the right side of the graph like we do above, we can actually have it align to how we perceive pitch relationships more easily because if it weren’t like this - if it were linear - almost all of the display would be used for high frequencies, well above where we’d normally play our melodies where vocals sit, etc. It just wouldn’t be useful.

Bada-dap-bap #

Okay, so we know music is made up of these waves with different flavors and that we usually change this flavor over time - at least enough that it can decay out. But unless you’re considering the truly avant-garde, a single note being played isn’t really music. Soundscape or ambiance, sure, but not “““music””” in the traditional sense at least. Where most people draw that line is by the inclusion of repeated rhythmic structure.

Note I said Rhythmic and not Melodic. You can have music that lacks note changes and instead only uses a repeating sequence of un-tuned drum hits, for example. A lot of rap and hip-hop will do this, yet some royal asshat’s will gate keep this because, frankly, racism.

You’ll typically have both rhythmic and melodic elements. And, typically, each sound is doing a little of both and interacting with one another. But let’s think about what each really means.

Rhythm, at it’s core, is what time do you hit the note, but most people will also consider how hard you hit it. If you read duh-duh DUH. You probably grouped those first hits and made the 3rd one both later and louder. That’s Rhythm.

Melody, is your basic do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti scale walk (or whatever is typical in your culture). You may not do it with any rhythmic complexity at all (each space equally in time, at the same volume, etc. ) but there’s still melody there. This can include more though, like pitch bends, vibrato (pitch wobble), etc.

Where you choose to draw the line of what to consider part of the melody or rhythm doesn’t really matter much in the end, what does matter is that you can use them to convey what you want to convey, be it a high energy moshpit banger or a sad song about love and loss.