Chapter 37.2 - The OSI Model #

The OSI model of networking is the model of networking most classes will cover. It is slightly different from the one used by the internet, which is the TCP/IP model, but it’s a bit more regularly used when talking about networking, so it’s the one I’ll cover here. Note, the big difference is really just that In the TCP/IP model, the Physical and Data Link Layers are viewed as a unified ‘Network Acces Layer’, the Network Layer is called the Internet Layer, The Transport Layer stays the same, and the and The Session, Presentation, and Application layer are all part of a larger Application Layer.

Seriously though, don’t think about this to much. It usually doesn’t matter and the OSI Model is fine.

1 - The physical Layer #

The series of tubes, wireless media, etc. that you shove your information into

We’ve already talked about Routers, Switches, Hubs, Nodes, and Links - all of these are part of the physical layer. Let’s look at some of the details though:

Ethernet is not on the physical layer #

First, let’s get a point of confusion out of the way, Ethernet is not the connection standard. The rectangular-ish plug with 8 wires often carries Ethernet, but the plug you’re thinking of is, just 4 pairs of wires with two RJ45 connectors usually connected via Cat rated cables.

The wire itself often has a rating such as Cat5, Cat5e, Cat6, Cat7, etc. Generally, bigger number (or +e/A) means you can get it to go further or carry higher bandwidth signals (for example, 2.5, 5, or 10 gigabit Ethernet) before the noise in the wires kills everything. See cablek.com’s handy, based on their HTML probably stolen, tables.

But, again, not all Ethernet signals are carried over those wires. Historically, it was often carried over Coax (same wires as you’d use for connecting a TV antenna), and in modern times you’re likely to see SFP cables used for the really high throughput stuff (100GbE+, for example.). Those may use copper, or they may be direct fiber connections - because - again - Ethernet is a layer up. We’re still at the physical layer.

All of that said, please still call it an Ethernet cable.

What about PoE?

Power over Ethernet, or PoE, allows network cables to carry electrical power. This means that network devices such as routers and switches can be powered through or provide power via the same cables that are used for data transmission. This can be convenient because it eliminates the need for separate power cables, which can be difficult to install. PoE is commonly used in applications where it is not practical or possible to provide power to network devices through a traditional wall outlet, such as for security cameras. The technology is also often used to power IP cameras and other networked devices that require a power source.

The standard is a bit of a fustercluck. There’s a decent char on the Wikipedia page detailing the voltages, currents, cable requirements, max power, etc.

Wi-Fi #

Wi-Fi is a part of the IEEE 802.11 standard and normally uses 2.4GHz and 5GHz. Very recent developments are pushing it into 6Ghz for most uses. There are some less common variants of WiFi that use 60Ghz (WiGig, CMMW) and sub 1Ghz (Wi-Fi HaLow, White-Fi).

WiFi, like ethernet, is really a mix of being at the Physical Layer and the Data Link layer. On the physical layer, the main thing we should think about is the frequency it’s running at. So, we normally call WiFi either 2.4Ghz or 5Ghz. So, it must run at those frequencies, right?

Sorta. There’s two gotcha’s. First, no, it’s actually 2.401-2.495GHz and 5.030-5.990GHz, but more importantly, you won’t be using those full ranges anyway. For 2.4, that range is split up into 14 different channels (Wikipedia), not all of which can be used everywhere. Generally, on 2.4, you’ll want to be using 1, 6, or 11 as otherwise the channels will overlapp.

Image from Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA by Michael Gauthier & KelleyCook

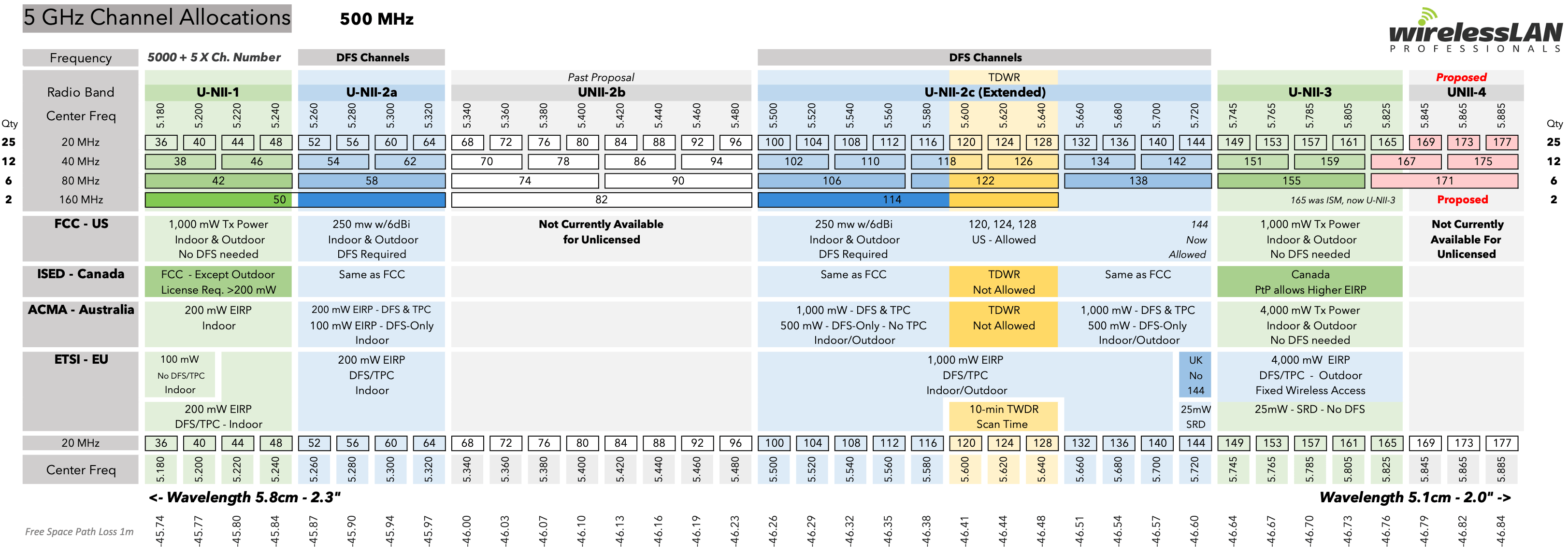

On 5Ghz, the channel situation is dramatically more complicated. There’s a who fuckload of channels (which you’d’ve seen on the Wikipedia channel page) but only a subset are used. Let’s go grab a picture.

Image stolen from https://wlanprofessionals.com/updated-unlicensed-spectrum-charts/ with love ❤️, Seriously, I can’t even imagine how much of a pain in the ass this was to make.

If you look at the smallest channel blocks available, you’ll see they start at 36 and go up by 4. Each of those channels is 20MHz wide. Then, below 36 and 40 there’s channel 38. That’s a combined channel. Basically, it glues the two together to allow for more bandwidth (hence the name, it’s a wider band) thus more data throughput, at the cost of slightly worse range and more likely to be bothered by interference. Then there’s the 80Mhz band which is two of the 40Mhz bands glued together, and finally the big-boy 160Mhz which glues 8(!!!) regular channels together, yielding amazing throughput.

Of course, each band has it’s own power and licensing concerns, which are shown in that image as well.

Actually, the same is true of 2.4GHz - I already mentioned that you can use all the channels in every country, but you also are limited in power depending on region too. Yay! Regulations!

As if this wasn’t already complicated enough, the WiFi standard itself is evolving, supporting more physical layer features as well. Notably, these include MU-MIMO and OFDMA which are both black magic essentially boil down to making WiFi capable of handling more clients on a network with better speeds. Fun stuff.

Oh, and Wi-Fi 6E is slowly rolling out, which adds yet another frequency band for us to get confused by. Still, it’s more speed for our devices, so it’s a win.

| Generation Name / IEEE Standard | Year | Frequency Range** | Max Rate | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wi-Fi 6E (802.11ax) | 2020 | 2.401-2.495+5.030-5.990+“6Ghz”(5.925-7.125Ghz) | 9608 Mbit/s | The “E” is to denote this extra spectrum |

| Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax) | 2019 | 2.401-2.495+5.030-5.990GHz | 9608 Mbit/s | dramatic under-the-hood changes: notably OFDMA, more spatial streams, and uplink MU-MIMO |

| Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac) | 2014 | 5.030-5.990GHz | 6933 Mbit/s | Allows for wider channels, MU-MIMO, Beamforming |

| Wi-Fi 4* (802.11n) | 2008 | 2.401-2.495+5.030-5.990GHz | 600 Mbit/s | Adds basic MIMO, Spatial Division Multiplexing, frame aggregation, and possibility for 40Mhz channels |

| Wi-Fi 3* (802.11g) | 2003 | 2.401-2.495GHz | 54 Mbit/s | Basically a speed bump from Wi-Fi 2. Runs slower if there are any Wifi 1 devices on the network. |

| Wi-Fi 2* (802.11a) | 1999 | 5.030-5.990GHz | 54 Mbit/s | Basically just defines the addition of the 5GHz band |

| Wi-Fi 1* (802.11b) | 1999 | 2.401-2.495GHz | 11 Mbit/s | Yes, b is worse than a, but was short lived- you’ll mostly see b/g/n support on low end devices. |

| Wi-Fi 0* (802.11) | 1997 | 2.401-2.495GHz | 2 Mbit/s | Initial spec, Extremely rare |

If all of this feels really abstract, go grab the WiFi Analyzer app and checkout all the signals around you. You can see what’s operating on what channel and maybe move to another one so that you and your neighbor’s signals aren’t trying to scream over each other.

More about those weird standards:

Generally, transmitting at higher the frequency will yield worse range but higher data throughput. This isn’t strictly true, but it’s mostly true.

| Generation Name / IEEE Standard | Year | Frequency Range** | Max Rate**** | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (802.11y-2008) | 2008 | 3.65-3.7Ghz | ??? | A spectrum licenseing shit storm, can run at higher power |

| (802.11j) | 2004 | 5Ghz only | ??? | Mostly Japanese. Might(?) be used in the US by Law Enforcment? |

| WiMax (802.16) | 2005(802.16e) | 2-11Ghz | ~40 Mbit/s normally, 1Gbit/s for fixed stations | Spectrum used may require license. Hardware is actually available. |

| White-Fi (802.11af)*** | 2014 | 755-928Mhz | 35.6 Mbit/s, 426.7 Mbit/s with channel bonding –extremely variable | Also known as “White-Fi”. Uses Licenced Spectrum. Also see 802.22 |

| Wi-Fi HaLow (802.11ah)*** | 2017 | 900Mhz | 150Kbit/s to 78Mbit/s – extremely variable | Also known an Wi-Fi HaLow. Some consumer products available, dubious legality |

| CMMW (802.11aj) | 2018 | 45Ghz | ~15Gbit/s | Mostly used in China, CMMW = Chinna Milimeter Wave |

| WiGig (802.11ay) | 2021 | 57.24 to 70.20Ghz | 277(?)Gbit/s - (When running with basically all of the spectrum dedicated to one link) | Extension of ad |

| WiGig (802.11ad) | 2012 | 57.24 to 70.20Ghz | ~7Gbit/s | Used by Dell and Lenovo for a bit, hardware compatability & drivers may be rough |

Also note, WiFi generally uses the same 2.4Ghz spectrum as Bluetooth (IEEE 802.15.1) and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE, not from an IEEE standard).

This is not all of the 802.11 standards. There’s a bunch of extensions/application specific cases like 802.11p for use in moving vechicals

SSIDs - Service Set Identifier #

A WiFi SSID is the name of a wireless network. It is essentially a unique identifier that allows devices to connect to the network. When you set up a wireless network, you will typically be asked to choose a name for the network, which will become the WiFi SSID. This name is then broadcast by the router so that nearby devices can detect and connect to the network. The name can only be up to 32 bytes long. You may be able to set it to use Unicode, but you proably shouldn’t as it can really fuck shit up.

It is possible to have a hidden network with no SSID.

Multiple Acccess Points, Repeaters, #

Security #

WEP, WPA(v2), EAP, TKIP, RADIUS, PEAP, LEAP —> Maybe redirect to security chapter

Not Using Wi-Fi #

Ethernet over power, wired tethering (USB)

Other Wireless Systems #

Satelite, geostationary & LEO

End to End Delay #

d_ECE = 2 (L/R)

where L = bits per packet, R = tx rate of link

Queuing Delay #

Hubs, Repeaters, Taps #

Carrier Pidgeon, Can, etc. #

+ Sneakernet, Infiniband, Multigig

Modems? #

[TODO] http://www.whence.com/minimodem/

2 - Data Link #

Organize the information in the meduium into a packet, control who get’s that packet

MAC and LLC

Ethernet #

PPP - Point-to-Point Protocol #

Switch #

Bridge #

Frames #

VLAN - Virtual LAN #

3 - Network Layer/IP Layer #

Find paths though the mesh of links and forward the packets though it

Service Models #

Not guaranteed delivery, bounded delay, or throughput. Sorta sucks, but it’s cheap

Packets #

IPV4, IPV6 #

IPV6 is a total nightmare & Hacker News comments on this blog post (note, I don’t agree with everything here, just providing it as another person’s comments)

IPV4->6 Tunneling

Logical: [6] <-> [6] <- ——————- -> [6] <-> [6]

Physical: [6] <-> [6] <-> [4] <-> [4] <-> [6] <-> [6]

It’s very reasonably to scan literally every IPv4 address. See A Census of Minecraft Servers or Harder Drive for examples of this being done.

MAC #

ICMP - Internet Control Message Protocol #

https://xkln.net/blog/icmp-ping-and-traceroute--what-i-wish-i-was-taught/

IGMP - Internet Group Management Protocol #

traceroute

Subnets #

https://www.aelius.com/njh/subnet_sheet.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subnetwork

Static and Dynamic Routes #

BGP - Boarder Gateway Protocol #

BGP is one of those things that you should basically never have to worry about, and if you do, it’s almost certainly because somebody else fucked up. That said, it does still matter. In 2021, a BGP mis-configuration took FaceBook down globally and in 2008 Pakistan used a BGP hijack to take down YouTube. But, uh, what is it.

Well, if you’ll allow me to follow the lead of the late Alaskan Senator Ted Stevens’ less-than-ideal analogy: “The Internet is a series of tubes!” and BGP is the logic that dictates where things get routed to go from one tube to the next, and tries to adapt to find the fastest, most efficient route when there are multiple available paths, but, while I could try to explain it, This article from Cloudflare will do a much better job than I ever could, so just, read that and come back here.

Hai, welcome back - so, okay, BGP is only something for the ISPs and big players, right? Well, no.

First of all, you might, occasionally want to check something isn’t taking a very stupid route, which means digging into BPG yourself. Julia Evans wrote a great blog post “Tools to explore BGP” that does a good job of showing how to poke around things. If you actually want to get hands on, you can use GNS3 to simulate a network, or join https://dn42.eu/ to try something more tangible.

There’s some fantastic other pages I recommend reading too. Most notably, EVE Online internet from https://blog.benjojo.co.uk is a really neat look at BGP and just a fun read!

BTW, Ben Cox blog has a ton of other really neat posts, like The Speed of BGP network propagation, BGP Stuck Routes, and Hacking Ethernet out of Fibre Channel cardsTo finish things up, the Wikipedia article for BGP is quite nice as well, and does a really good job of explaining the more technical operation in plain english.

4 - Transport Layer #

Better reliability of the network by keeping packets in order, retransmitting lost packets, etc.

Multiplexing, Demultiplexing

Reliable data tx/rx - checksums

flow and congestion control

TCP - Transmission Control Protocol #

https://research.swtch.com/tcpviz

tcp header diagram

https://github.com/appneta/tcpreplay

UDP - User Datagram Protocol #

QUIC - Quick UDP Internet Connections #

Raw #

A brief dive into FSMs #

Go-Back-N #

Selective Repeat #

Timeout and Retransmission from Estimated RTT #

5 - Session Layer #

Authentication #

Sockets #

API - Application Programming Interface #

NetBios - Network Basic Input/Output System #

PAP - #

RPC - Remote Procedure Call #

SMB - Server Message Block #

SOCKS - Socket Secure #

6 - Presentation Layer #

SSL - Secure Sockets Layer (Deprecated) & TLS - Transport Layer Security #

SSL and TLS are cryptographic protocols that are used to secure communications over the internet. SSL, which stands for Secure Sockets Layer, was the first widely-used security protocol, but it has since been replaced by TLS, or Transport Layer Security. Both SSL and TLS encrypt data that is transmitted over the internet. They are commonly used to secure web traffic. In order to use SSL or TLS, a web server must have an SSL/TLS certificate, which is used to authenticate the server and establish a secure connection.

IMAP - Internet Message Access Protocol #

IMAP is a protocol used for accessing email messages on a remote server. It allows users to retrieve email messages from a server and manipulate them as if they were stored locally, without actually having to download the messages to the user’s computer. IMAP is usually used in conjunction with a mail client, like Outlook or Thunderbird.

7 - Application Layer #

HTTP(s) - Hypertext Transfer Protocol #

https://fasterthanli.me/articles/the-http-crash-course-nobody-asked-for

http://bright28677.tripod.com/proj2/httpformat.htm (both images)

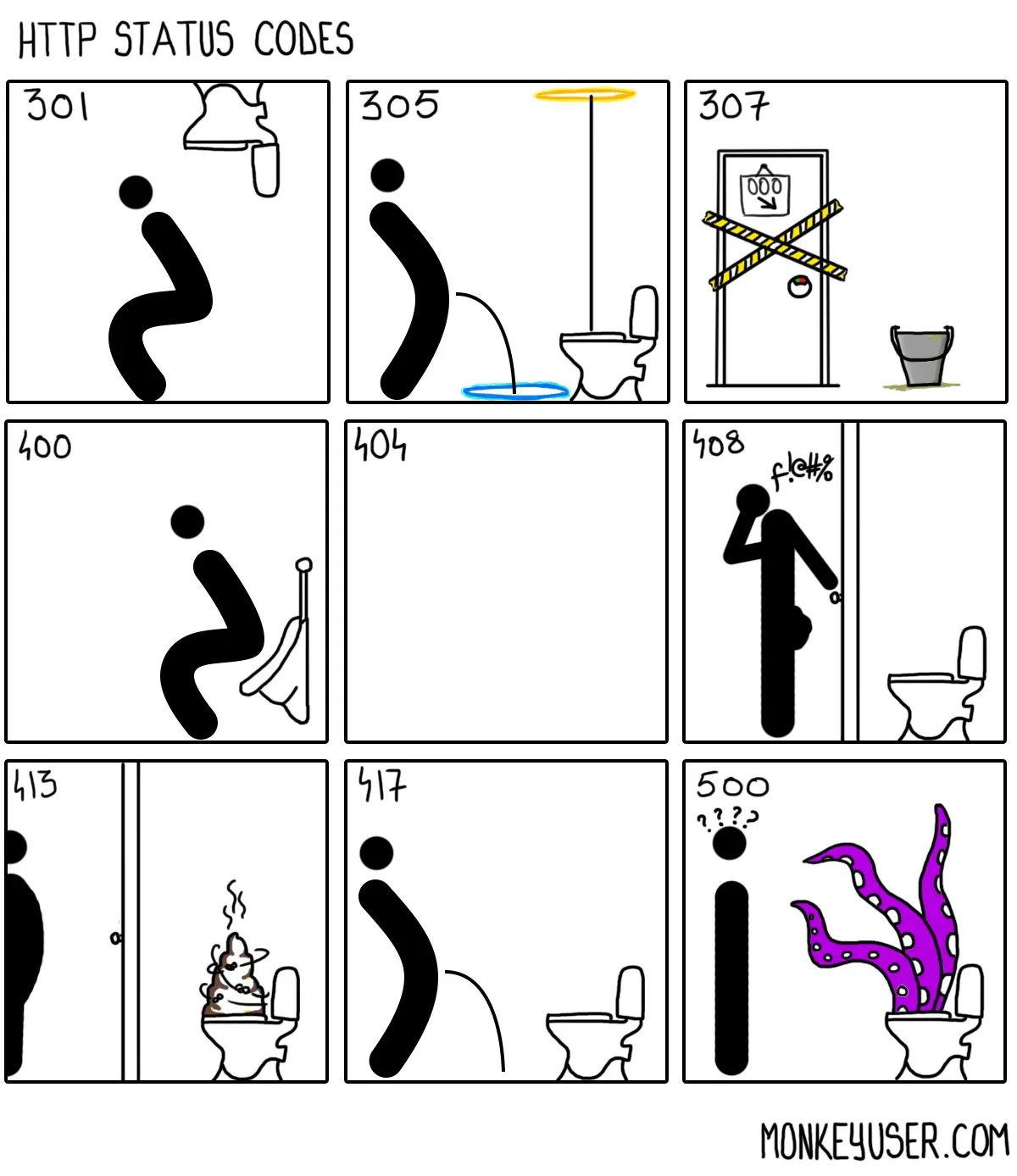

response codes - 200, 300’s, 400’s, etc.

In header lines

Host, user agent, accept-language, connection (keep-alive), …?

GET, POST, HEAD, PUT, DELETE

http1 vs 2 v 3

cookies because stateless

in-band

FTP - File Transfer Protocol #

still TCP, out-of-band, maintains state, passive v active mode

DNS - Domain Name Service #

Not All TLDs Are Created Equal (Matt Palmer)

TTL?

DNS TTL, or Time to Live, is a value in DNS records that determines how long a DNS resolver is supposed to cache the DNS record before it expires and a new query is made to the DNS server to refresh the record. This value is set by the owner of the domain and is specified in seconds. A low DNS TTL value means that the DNS resolver will refresh the record more frequently, while a high DNS TTL value means that the record will be cached for a longer period of time before it is refreshed. This can be useful for managing the load on DNS servers and ensuring that users always have access to the most up-to-date information about a domain.

Stop Using Rediculously Low DNS TTLs (Frank Denis)

record types

You Smart TV is probably ignoring your PiHole (LabZilla)

72% of Smart TVs, 46% of Consoles hardcode DNS Settings, (Hacker News Comments on article)

Bonjour / Zeroconf #

Occassionally, you may find things that want a name given to them by the local system. If two systems are running Bonjour / Zeroconf, then you can have a local name that should always point to the device. This is particularly handy for setting up devices like the Raspberry Pi Zero as a USB gadget and letting it show up as a network device on the system it’s plugged into- now it’ll have a local name. See Bonjour (Zeroconf) Networking for Windows and Linux (Adafruit).

DHCP - Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol #

Some texts will put this in Data or Network layer or Link Layer, it’s a bit ambiguous. It’s not -technically- necessary, much like DNS, but it’s used as a core part of the network in most networks. It does appear the RFC 2131 says it’s Link Layer, but it seems most people think it belongs in Application Layer.

SSH - Secure Shell #

SSH is mostly used to remotely access and manage servers, as it provides a secure way to connect to the server and work via a command line. It is also often used to securely tunnel other network protocols, such as FTP, Telnet, and VNC, over an unsecured network.

IRC - Internet Relay Chat #

EMail (SMTP, IMAP, POP) #

mail servers and useragents

UPNP - Universal Plug and Play #

NTP - Network Time Protocol #

NTP is a protocol used to synchronize the clocks of computers over a network. It allows devices on a network to maintain accurate time by periodically synchronizing their clocks with a reference time source - there’s plenty of free NTP servers, such as those run by NIST.

Having correct time is important because many network protocols and applications require accurate time in order to function properly. For example, the correct time is needed for generating log files and for ensuring that cryptographic signatures are valid.

Telnet #

NFS - Network File System #

Torrents #

Distributed Hash Tables

Time #

Real time clocks, timezones, utc, etc.

No Good Place In The Model: #

VPNs #

OpenVPN #

Wireguard #

Wireguard entry on the (Arch Wiki)