Chapter 6½ - Units #

Units are a really big deal. A single missed unit conversion in The Mars Climate Orbiter made the mission a failure which cost $327 million in 1998.

Or it could just mean you’re overpaying on your phone bill, since it seems nobody at Verizon knows the difference between .002¢ and .002$.

I could dig around and find more funny examples, but on a serious note, you’ll end up dealing with units a lot in pretty much engineering discipline.

You probably have at least some practical experience with unit convesion for the few things most people see commonly:

C ↔ °F

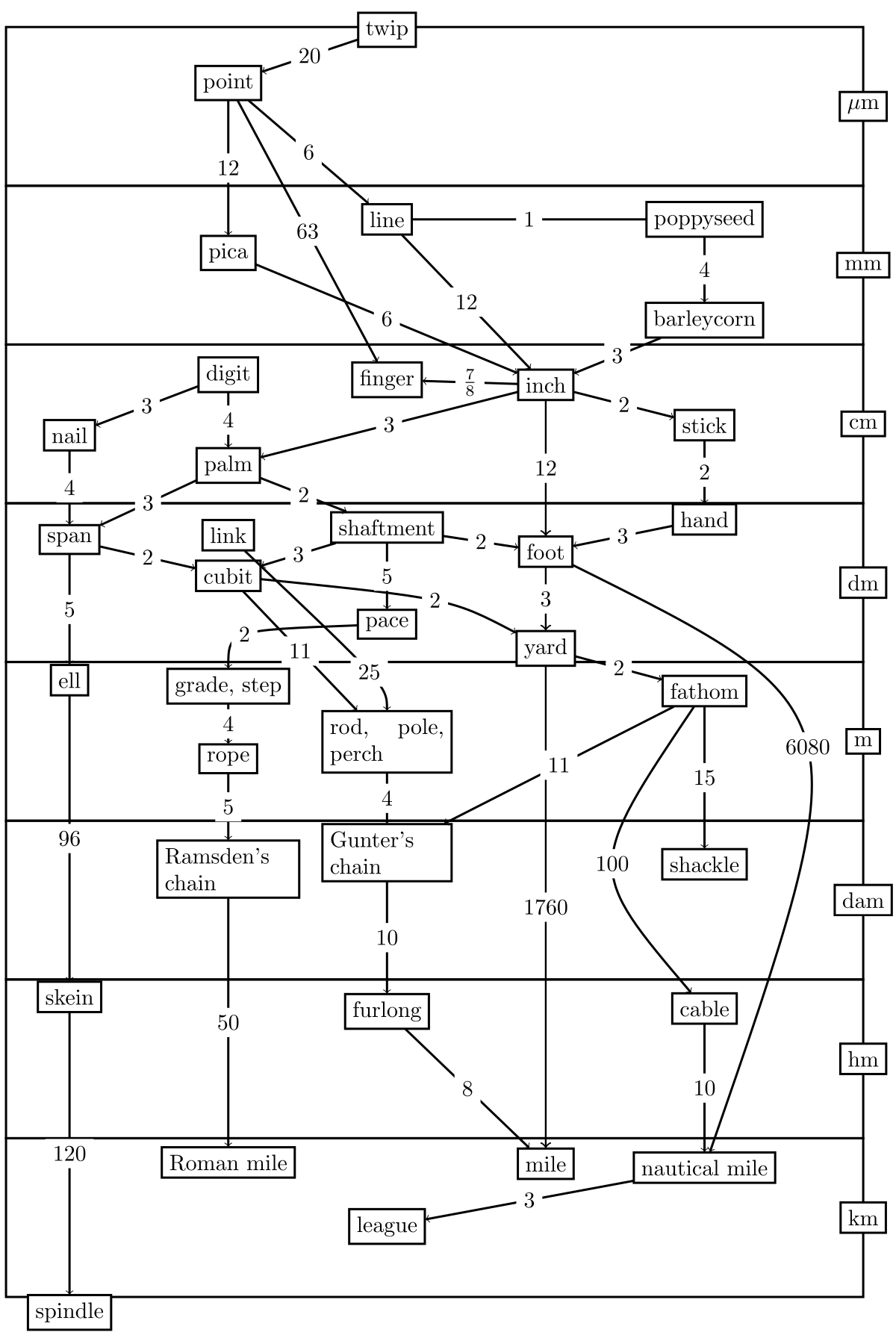

Ft ↔ M

Mi ↔ Km

To deal with those, it’s almost always what you’re used to, just multiply or divide by some number. For some units you also have to add or subtract a constant - like doing C ↔ °F

The other thing you’re likely to see though is converting between scales of units. So, lets dig inot that:

Scaling, Logarithms and Scientific Notation #

Many units have a scale attached. For example, the meter - you have killometers (1000 meters) and centimeters (.01 meters) - so we need to discuss scale. That is, the idea of how big or how small something is, usually relative to something else.

In elementary school, you were taught to write the powers of 10 like this:

1

10

100

1000

That is good for regular numbers, but it works against us when we are dealing with numbers that are similar, and all of them are either very large or very small.

To avoid this problem, it is better to use scientific notation. With this, you normalize your digits so there is exactly one before the decimal point, and then use “E” as an exponent marker on a power of ten. The number of digits indicate significance, but that is a separate section.

| Scientific Notation | Value |

|---|---|

| 1E0 | 1 |

| 1E1 | 10 |

| 1E2 | 100 |

| 1E3 | 1000 |

| 3E0 | 3 |

| 2.2E2 | 220 |

| 1.88E4 | 1880 |

Each power of ten also has a prefix in the SI system. For example, with meters:

| Quantity | Value |

|---|---|

| 1E0 m | One Meter |

| 2E1 m | Two Decameters |

| 3E2 m | Three Hectometers |

| 4E3 m | Four Kilometers |

Most likely, you had a science teacher in high school or college make you do this at some point. But they probably didn’t explain how useful this is an aid to intuition, not just calculation.

Reading Graphs #

Here is an example of a graph in linear scale: worldwide COVID cases through late 2021.

With linear scaling, the units on the vertical access become smaller the bigger the range of the data becomes. For a high-level trend, this in fine. But what if you wanted to examine the first year? With exponential growth processes like disease, that is important.

Consider the logarithmic view instead:

In a logarithmic view, a straight line indicates the slope of an exponential growth curve. This graph shows the base of the curve changing over time.

This makes it easier to identify the path and the pace of the spread. From cases 1 to 50,000 was just as fast as cases 100,000 to 1 million, as one would expect from an exponential process that is rampant and unchecked. Once mitigations and later vaccines became common place, it slowed down, and stopped being exponential, being much closer to linear in behavior.

You can see this “square root” curve tail, which means that its speed is indeed slowing down based on the size of the numbers – in other words, linear growth.

This should help to illustrate why logarithms are useful: just like scientific notation, they are “scale free”. Big numbers and little numbers take up the same amount of space, and it is the ratios and relative rates of change that are the most significant features of the shape.

For problems with wide ranges in scale, they are an excellent tool to examine details where scale does not matter.

Unit Prefixes #

If you live in a metric country, you know how long a meter is from your regular life. Unless you have done a lot of EE work, you have no idea “how big” an Ampere is.

But with this system of units and powers, you don’t have to. You only need to know the prefixes, and use whatever numbers you are given in your calculations. You can then compare things with ratios to something you do understand.

The most common prefixes are not multiples of ten, but multiples of one thousand – and with EE, usually in the smaller direction:

| Quantity | Prefix (meters) | Shorthand |

|---|---|---|

| 1E0 | Meter | m |

| 1E-3 | Millimeter | mm |

| 1E-6 | Micrometer | μm |

| 1E-9 | Nanometer | nm |

| 1E-12 | Picometer | pm |

| 1E-15 | Femptometer | fm |

Millimeters are the smallest one can possibly use in day-to-day life without special equipment. But to a nuclear physicist, the Nanometer is the moon’s orbital distance compared to our own height.

As a result, math becomes a convenient abstraction in order to hide the complexity, while guaranteeing good results. After all, if you have two numbers in scientific notation, you simply multiply the base numbers (e.g. 2.5) and then the exponents (e.g. 10^3, and in algebra, that means add their exponents).

Whatever you get, you get, and it will be the correct answer.

An example problem #

Imagine that you are creating an embedded device that will be powered by USB. You decide to use an Arduino to start, because it’s easy to program, but also it’s relatively low power.

Still, you know it’s low power because it does not have a very fast CPU. Perhaps a bigger board would be better. How does the power it draws compare to the power you have available?

You measure the amperage flowing down the USB cable and discover it is 18 mililamps. How much power is it using?

According to Ohm’s Law, the power being dissipated by an electronic device is its voltage drawn multiplied by the current measured passing through it. The USB bus is normally 5V, and for the back-of-an-envelope calculation, we can just assume that.

In scientific notation, the calculation becomes:

= 5E0 * 18E-3

= (5 * 18) * (10^0 * 10^-3)

= 90 * 10^-3

= 9E-2

= 0.09 Watts

= 90 milliwats

How much power is that? What does that number even mean?

To make sense of it, consider something we have a sense of: the amount of power that can come out of a US wall socket before it overloads and a breaker trips. They are rated at 120 Vac and 15 Amperes.

Using Ohm’s Law:

= 120 * 15

= 1800 Watts

= 1.8E3

= 1.8 Kilowatts

Assume there are no losses in conversion, a wall circuit could power 20,000 of your boards before tripping a breaker. So that suggests it’s pretty small.

But what about a USB port? That can’t produce nearly as much power. But if you look it up, a single USB port is supposed to be able to generate 2.5 Watts of power. So if someone were to use an unpowered hub, then they could plug in 27 of your boards before the USB was overloaded.

In other words, an Arduino is very low power for this application. If you need more CPU cycles, you can use a bigger board.

[TODO] - weird units coming up: moles, ferads, light years, pascals, radians+, electron mass, big/small metric units, flops, decades, etc.

References #

More fun problems of intuition, including probabilities, can be found in Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences