Time Based Effects #

Delay #

There are a million ways to make a delay that’s weird. Most basic? Make a ring buffer and add the signals, probably with a dry/wet mix. Less basic? IDK, add in multiple taps on the ring buffer? Use random samples in the buffer? Change the sample rate of the buffer? Reverse the buffer occasionally? Go nuts.

Delay is basically echo. Take a sound in, and repeat it it it. Normally the main controls on a delay are ‘Time’, which controls how long of a delay there is before each repeat, ‘Feedback’ which controls how much the level is reduced each time the delay repeats (and in turn, how many audible repetitions there are), and ‘Dry/Wet’ which controls how the signal is blended, entirely dry will have no delay, entirely wet may even miss the initial sound adding a weird latency before you hear what you’re playing. Some delays have additional controls, obviously I can’t cover every possible delay, but I’ll try to cover most:

Some delays instead of letting you set a delay time or ’tap’ a delay tempo in to actually synchronize to a clock signal input which lets the delayed repetitions always be in time with the rest of the song.

Stereo delays many have additional controls as well, most commonly offering a different delay time for the left and right channels. Often a ‘Ping Pong’ mode will also be available where the left and right speaker alternate for the repeated sound- ‘ping’ and ‘ponging’ out each side until the sound cuts out.

Some delays may also allow for unity or higher feedback, which will cause the delay to be infinite or, if above unity, infinitely grow in volume until it’s just a distorted clipping mess. This can actually be a lot of fun to play with.

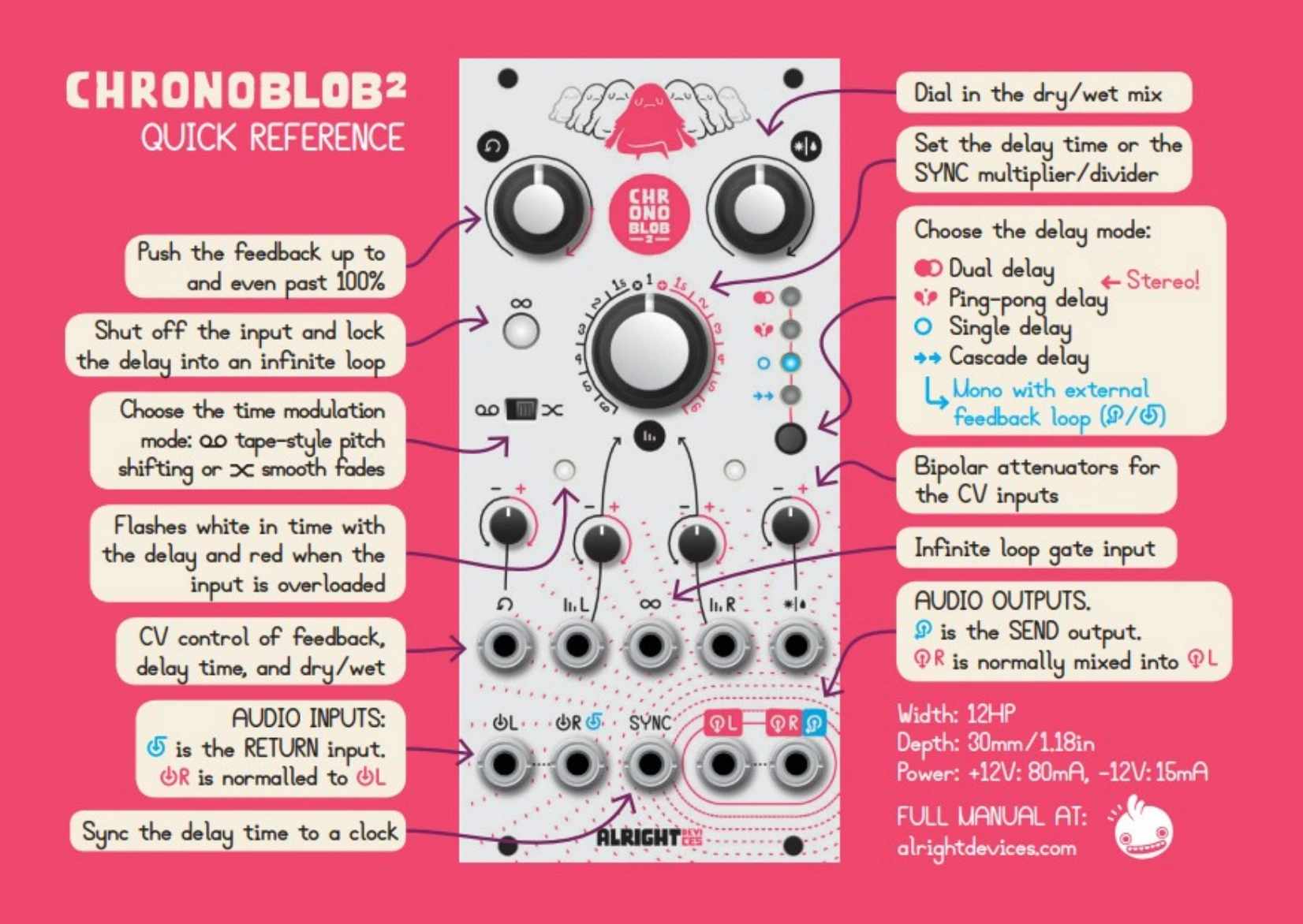

From the Quick Reference Card for the Chronoblob 2 from Alright Device

Some delays let you insert other things into the feedback path. This means you could do things such as having each repetition be progressively more filtered, cutting out more and more high end each time or putting a delay in the delay. (yo dawg, I heard you like delay?).

Some digital delays and most analog delays (especially bucket brigade delays

There’s also a demo of over unity gain at the end. I’ve edited the volume of that, but it’s still a bit alarming!

Finally, it’s worth noting that there are a few interesting features some delays may have, such as letting the delay buffer be frozen to infinitely repeat what was playing at the time (unity gain, ignore input), reverse’d delay - having the initial sound play forward but each repeat play in reverse, pitch shifted delay- having each delay affected by a pitch shift, often done with octave up/down. Often, this pitch shifting is done via Granular Synthesis, as mentioned above. Using granular synthesis does allow for some other interesting options though, such as Unfiltered Audio’s Sandman Pro VST.

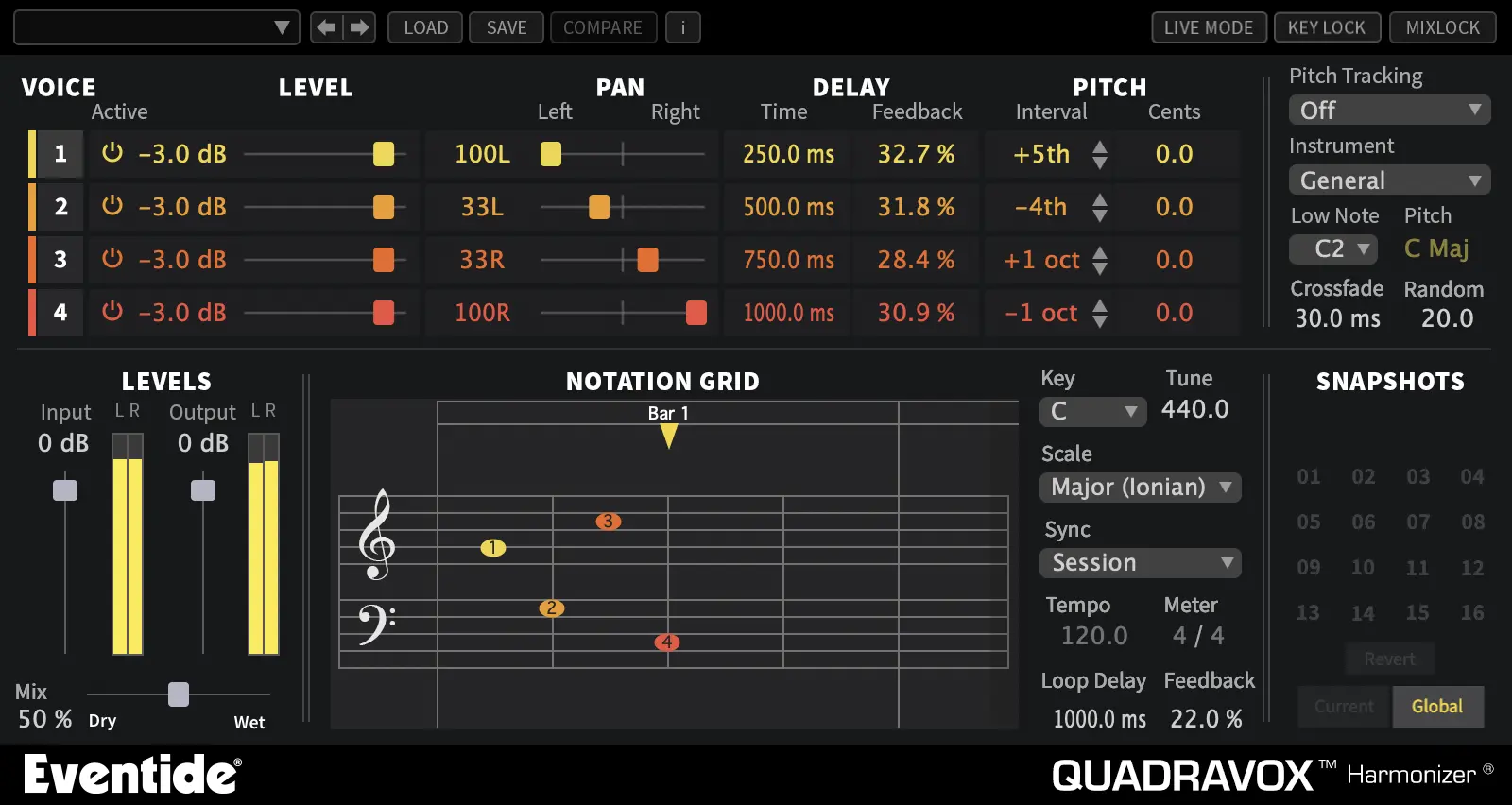

Screenshot of Eventide’s Quadravox VST, with pitch shifted delays

Slapback delay #

Slapback delay is just a short delay with only a single echo, no feedback. It’s often used on guitar, but it’s nice on vocals and drums too! Here’s a little example with Mutable Instruments’ Elements as the source. The first few notes are the dry signal, then I bring it in.

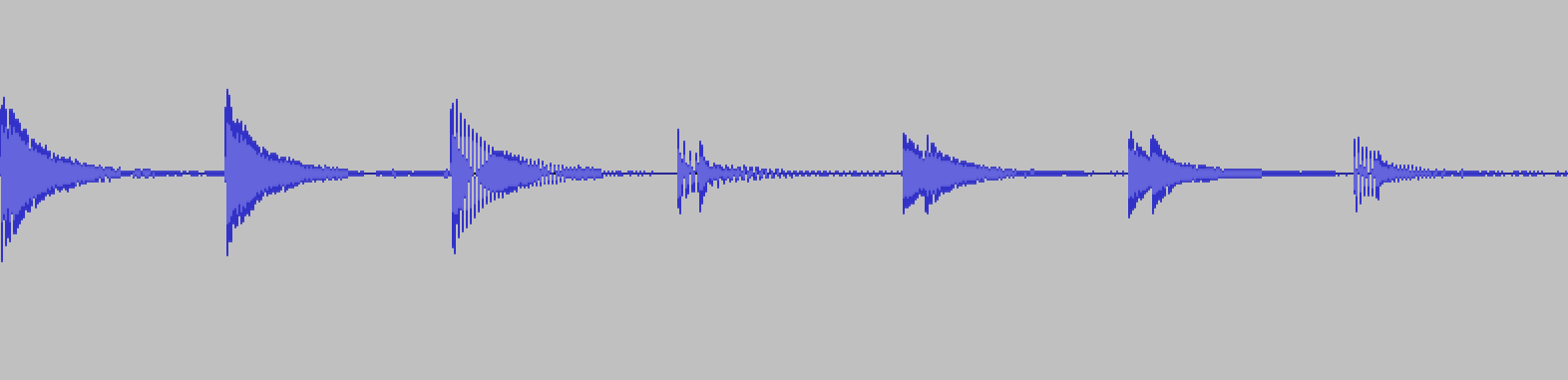

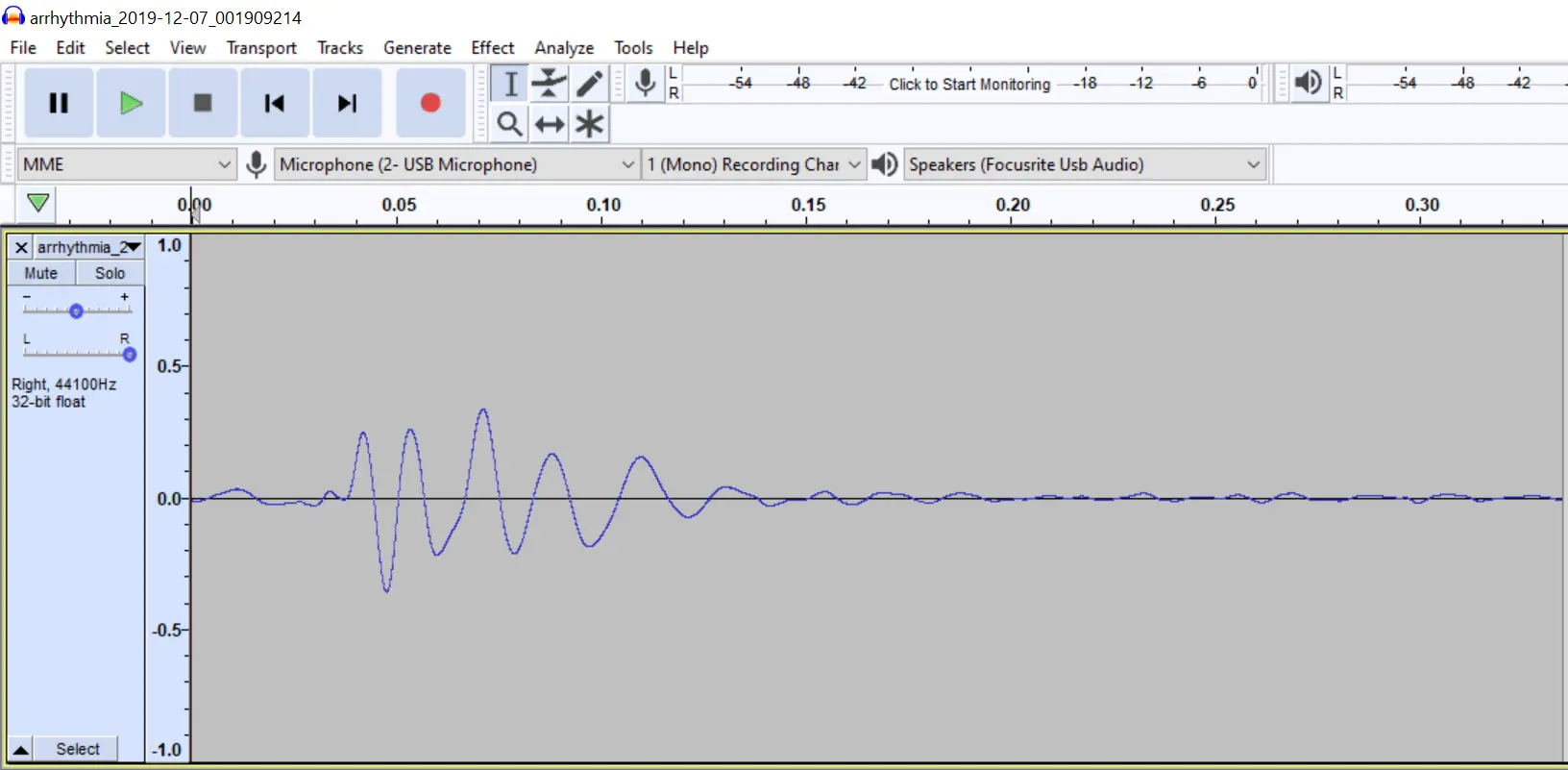

looking at a snippet of this audio, you can see just how short the delay is, with the slapback being on the notes that have the double hits.

Delay at 100%(+) feedback? #

Most delays will let you adjust the number of repeats but usually what you’re doing is adjusting how much volume each repeat should go down by. If you set each repeat to not loose any volume at all, the delay will go on forever. (Which can be very bad if you’re adding new stuff to the delay - this gets really loud, really fast!!) but it can be a really fun sound to explore. I recommend giving this one a shot. Try some different delays and see what happens as you max out the “repeats” or “feedback” knob.

Some will ever let you go above 100% to make each repeat get louder. This can get really crazy, so be prepared to quickly go “oh shit!” and turn it back down!

To see a good use of this in practice, check out My Secret Guitar Pad Patch from the 1990’s (Youtube, Dan Worrall), where he Inversely links volume and delay feedback.

Vintage Delays #

Bucket Brigade Delays #

Tape Delays #

Oil Can Delays #

Loopers #

Loopers are most commonly seen in hardware and can be seen as a sort of mix between samplers and delays. Essentially you just tap in when you start playing, play what you want, then tap out, then, the loop of whatever you played will play back to you. There may be additional settings, such as a half speed effect.

Often you’ll see loopers used for ‘Live Looping’ performances, where each layer is looped and overdubbed to create a full song

Here for example is a jam using the Ditto X4 looper (the box slightly blurry, closest to the camera), which is used to loop the guitar here.

Reverb #

The DSP for reverb is a black magic. If you actually want to persue this, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Il_qdtQKnqk then go read ALL of Valhalla DSP’s blog post, then realize making a good algorithm is just thousands of hours of trial and error.

Reverb is the sound of a space. It’s the reflections of the sound waves off of everything around you - be it your shower’s walls as you sing or the vastness of a cathedral. It’s why singing into a well can sound beautiful (YouTube).

It used to be that to get good reverb in studios required literally playing in these spaces or recording the sound, piping it into a room made to have good reverb with a carefully placed speaker and mic, and recording the result.

Fortunately, today, we have really, really good digital reverbs.

Better, we have reverbs that can go places no reverb could before, letting you feel like you’re in a cave or (if sound could travel there) outer space. We can modulate the reverbs to make sounds that will blow your mind.

Rooms #

You’ll often see reverbs listed as ‘room’, ‘cathedral’, ‘cave’, etc. These are trying to emulate the sound of playing in a closed but real space.

Plate #

Spring #

Seriously, watch the above video, Why Huge Metal Plates Are on SO Many Songs (YouTube). Text is not the best medium for explaining how something sounds.

Convolutional #

When working with signals - which fundamentally is what making music is - there’s this mathematial process you can do called convolution. This is a bit hard to explain, so let’s start by looking at a drum hit’s waveform:

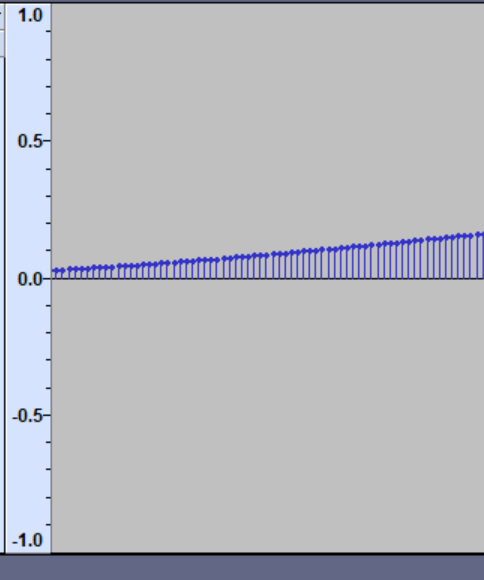

Okay, now let’s really zoom in:

We have all these tiny dots indicating the volume at that moment. In most recording we’ll have ~44 thousand of these dots per second. These are the values we’re telling the speaker to move to produce the waves. Cool, right?

Now, I want you to imagine we have only one little stem and dot. That’s a super brief “click!” though the speaker. This click is usually called an Impulse.

When you hear this click in your room, it will cause the room to echo a bit, and even if your brain mostly filters it out - you’ll hear the various things the room (and the speakers, for that matter) are doing to that “click”.

Now, if we make the assumption that the response to that click - what is really called an impulse response is:

- Linear - There’s a nice input-to-output relationship with regards to amplitude - A quieter input would just make the same reverb, but quiter

- Time-Invariant - The response to that impulse will be the same (or at least close enough, for reverb anyway) whever me make it

We can record that result and use it as a reverb. How? Well think of each point as the volume of the reflections from the room of the original sound at that moment in time. It’s like a map for when to play delays though the world craziest delay effect. But, we need that effect we can plug it into - that effect is called a convolution.

But, let me back up just a second:

Both of these assumptions are probably not 100% true. If you blast your speakers hard enough with that click, you may make things on the walls literally shake - clearly that’s not the same. Similarly, sound technically cares about temperature a bit, so, if you’re change the temperature during the day, time invariace also breaks down, but within reason, the assumption works. Reverb is, for most environments, close enough to being linear, time invariant that it doesn’t matter. The same is true of the sound of most guitar amp’s speakers - they will also color the sound in a way that shouldn’t care about the volume (barring extremes) or with time (barring significant aging)

But, note I bolded “speakers” that’s because the amp itself absolutely is not linear. Most guitar amps intentionally distort at higher volumes, and this distortion changes as it’s pushed harder. This will be relevent in a moment.

Okay, so, we have our impulse response. Usually, these will look (and sound) a bit like a drum hit if played normally, but they’re not intended to be played normally, the intent is to use them with convolution

The idea is you can take this new signal you’ve generated and scale it by the amplitude of each of those little points in your original recording and then keep adding these together. Basically, take your recorded impulse response and layer it on top of each point, scaled by the amplitude of that point.

If you recorded the impulse response of a room, it should sound like that room, and by adjusting how much you scale it you can choose how much of the effect of the room to apply. Of course, it doesn’t have to be the room you’re in. Somebody could send you the response for a cathedral, or a cave, or a parking garage. They could also send you the response of a guitar amp’s speaker. Or, someone could hand-craft a fake response to make a fancy delay. So long as the effect doesn’t have something in it that changes in time (like a phaser, modulated delay, vibrato, etc.) it can be recreated this way.

Of course, this also opens up a really weird option: you can use any recording (as long as it’s reasonably short) for this. You can use the sound of a drum hit as a reverb! It actually works surprisingly well sometimes!

But - I did just say “(as long as it’s reasonably short)” - what’s up with that?

Well, this if you’re making music with a sample rate of 44kHz (pretty typical) and the impulse response has 300 samples in it (still quite short) you’re asking your computer to do 13200000 multiplications a second. Now, that’s still not awful, but clearly, the longer the response, the worse it gets. If you have a 1 second response, that will be 44,000 * 44,000 = 1936000000 multiplications a second - again, on a modern computer its doable, just know it’ll eat your CPU.

This is one of the reasons why even if we technically could do a lot of effects via convolution, we often don’t.

But, even this isn’t totally true - if the response is long enough there’s a fancier way to do the convolution by using something called the FFT and transforming the both the impulse response and input signal into the frequency domain and then simply adding them together - don’t worry if you no idea what that means - The point is, we can replace all of that multiplications with a single addition! Sort of…

In reality, this is how it will be done for any remotely large impulse responses, but it’s not all sunshine and rainbows, that FFT bit actually pretty expensive for a computer to do too, espically at high quality. Plus, to keep latency down, the FFT has to be done pretty rapidly, so, even with the fancy-math to avoid it being out right infesibale amount of computations, convolutional reverbs still tend to be on the computationally expensive side - if you’re working on a laptop and want to run a bunch of virtual synths and other effects to, you may not have the heavy lifting required to run one.

Still, if you can get away with them, they do often sound extremely good. Usually you won’t get much control over them though as the reverb (or guitar amp speaker, or delay, or whatever) is basically baked into that recorded impulse response.

Shimmer #

A bit out of order here, but in a few pages we’ll talk about how you can use an effect to add an Octave up to a sound, adding a lot more high-end and an almost-synth like, two-instruments playing at once effect.

There’s a fancy way to use this where you shove the octave up effect into the feedback-loop of the reverb, causing these fading-in-volume but rising-in-pitch (or less commonly falling) tails

This demo from Valhalla DSP (YouTube) does a good job of showing what this is capable of.

Internals #

If you’re feeling particularly interested in this and want to learn more, I strongly recommend checking out this video which explains a bit about how algorithmic (basically any digital but not convolutional) reverbs are made:

Chorus #

Chorus does as the name implies, layering copies of the signal together to get a ‘denser’ sound. To be a chorus (and not just increase the volume) the copies are slightly pitch shifted, delayed, or otherwise modulated relative to one another.

Chorus tend to come in a lot of different flavors, so even if you try one at first and don’t love it, try some others. Magic Switch from Baby Audio is free and sound absolutely fantastic. I also recommend checking out Boss’s Dimension C pedal - or a clone of it. It has a particularly nice sound. Eventide’s TriceraChorus - available as both a pedal and a VST - is also quite go

See Time-Varying Delay Effects on DSPRelated.com for more about how this works.

Flanger #

Flanger works by taking a very short delay* which slowly modulated delay time and mixing this back with the original signal. This will result in some phase cancellation effects and give a similar sound to a phaser. The delay time modulation rate and depth, and delay feedback are the most commonly exposed controls. Flanger is probably most commonly used as an effect on guitar.

*note, that delay, in this context, means an actual time delay, just a buffer that makes sound take longer to get through if that makes sense. Of course, with feedback and mixing the original, this will have the same effect as a delay in the ’echo’ sense.

Flangers sort of makes a comb filter sound too, as you can see in the Spectrum Analyzer on the bottom.

The ‘Pyramids’ Flanger pedal from Earthquaker Devices.