Chapter 14 - Low Level Programming #

‘C Programming’ on badd10de.dev

Why C? #

This chapter of OpGuides will be mostly C, but, why? Well, there’s only really a few options for learning low level programming that make sense to start with. C, C++, Rust are the ‘big three’ that come to mind. C is what is most popular

To be clear, C has a lot of annoyances due to its minimalism. For example, there are no strings - only arrays of characters - and all memory management is manual. If you followed the programming intro chapters, you should’ve known that first part.

To be clear, writing low level code in C is what I do for work, so I’ve spent thousands of hours writing C with nothing but the standard library - so I’m not some noob that’s bitching from lack of skill. There’s a good reason Rust is taking over everything that was in C and it’s happening so quickly. I for one welcome our new Fe₂O₃ filled future.

Fortunately, once you know C picking up Rust or C++ should be easier, as they look relatively similar to C. Plus, learning C first will help you appreciate why they were made. Keep in mind though, they are different languages. C++ has features that you absolutely should use if you’re writing in it. Strings, abstracting out much of the memory management, ‘vectors’, etc. The same goes for Rust.

C also has a nice bonus for portability. You can call C code from Rust or C++ (as well as most other languages, with varying degrees of effort)

Don’t throw out everything you already know! #

Everything from the

“Lets Write Some Code”

chapters still applies. for and while and && and uint8_t - all of that jazz. If you need to review it, that’s totally fine. This page isn’t going anywhere.

Some simple programs, in C #

[TODO] use TCC instead of GCC, to enable live reload https://bellard.org/tcc/

[TODO] https://github.com/rby90/project-based-tutorials-in-c

[TODO] 30 Seconds of C++ (GitHub)

[TODO] http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/

Hello World! #

It’s traditional to start in any language by writing a program that just outputs the words “Hello World!” to the terminal, so let’s start there in C:

|

|

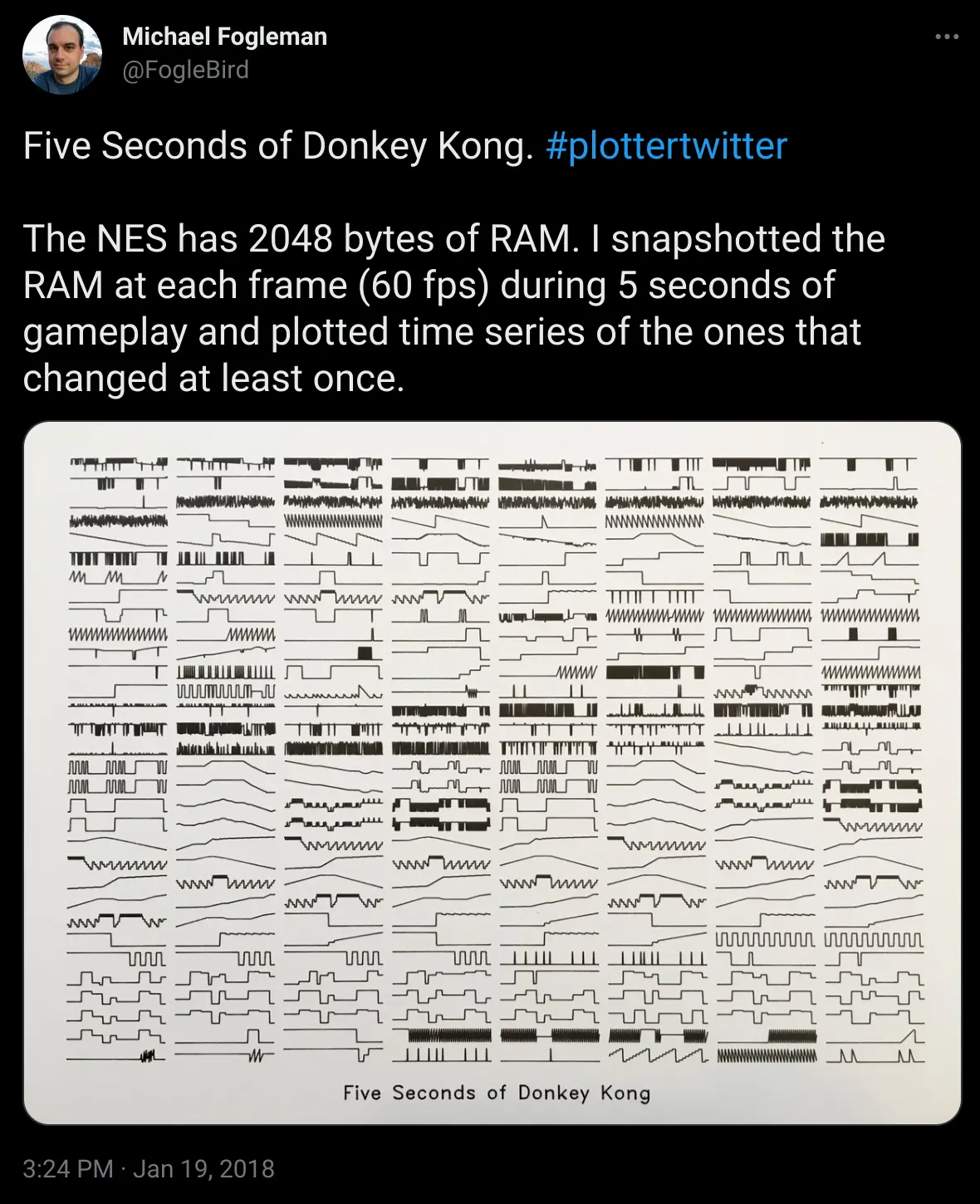

To run this code, save it to a file named hello.c and then open a terminal, navigate to that folder and run gcc hello.c -o hello, then you can run your program with ./hello, that should give you something like this:

[vega@lyrae ~]$ gcc hello.c -o hello

[vega@lyrae ~]$ ./hello

Hello World!

Alright, so let’s go through line by line.

On line 1 there’s a #include statement, this tells the compiler we want to include some library or other code. In this case we want the stdio library, as well need it in a few lines, but what about this library, where is it?

Well, that library is just some other code. Assuming you followed along with the rest of this site and are now running Linux, we can look at it by navigating to /usr/include/stdio.hor, in VSCode you can hold control and click on the word stdio to go its file, so let’s look at that file:

|

|

okay, so it starts with a big copyright block in comments - in C // makes a single long comment and /* comment */ are for multi-line comments - then on lines 39 and 40 we can see it is in turn including three more files such as stddef.h on line 33.

But let’s look deeper, down on line 332 of stdio.h we can see printf() is loaded as an external function. The extern keyword marks this as a sort of indicator to the compiler, gcc in this case, that this function definition is actually implemented elsewhere, but that this is the signature to expect from its usage. That is, when anything that imports stdio.h uses printf() it should expect to return an integer (the int before the word printf) and take in a pointer to a character array (the char * inside the parentheses) as well as a second argument of ... which is for a variable number of arguments

Woah, hold up, variable arguments?

Okay, yeah, this is a bit tangential but C does actually support functions with a variable number of arguments. You can recognize them by their declaration using an ellipsis (…) as their last argument.

For example,

|

|

These aren’t used super commonly outside of functions like printf/scanf but it is possible to write functions that use them yourself - it’s not magic. It’s just that normally you wouldn’t want to because there’s a lot of complexity in conveying type.

Because the arguments are variable, they can be whatever type they want but C doesn’t actually inform the function what type each argument is.

This is actually probably my biggest gripe about C. It makes writing type-generic functions require either:

- Duplicating code

- Using weird compiler macros like typeof() (which doesn’t do work how you’d want it to)

- Making an enum of valid types and passing a extra variable of that enum type in to indicate the type of the argument

All of these options are awful.

In printf the order of the different format characters like %d tells printf how to interpret each arg, but because it really has no idea what type you’re actually passing it there’s nothing stopping you from doing something weird like printf(%s, 3.14); - printing a float as a string (this has the potential to go very bad, actually).

varargs could easily be a whole page, but you’re better off just searching the web and reading up on them if you want to know more.

So, where’s the code for printf() that does the actual printing?

Well, in its part of libc. libc is the C standard library on Linux, typically it’s glibc in particular. This is a pre-compiled shared library so that when any program needs to use printf() it can just call the printf implementation from libc, which is stored in /usr/lib/libc.so.6

We could go looking into the source code for this, but I think it’s sufficient to say that it’s simply loaded from a shared system library.

Another thing you should notice is the #ifndef at the start of this file, which starts with a #, just like define.

These are pre-processor directives, just like #include is, basically, it’s special code that the compiler (in our case gcc) looks at before it complies the code. Of note there are #if and #else blocks, you might see these used for checking if a certain library is available for example, as a way to check what compiler is being used to adjust things slightly, or to check what OS the code is even being compiled for.

We’ve already talked about this a bit before when we discussed #define which is used to either set constants such as #define PI 3.14159 or #define GET_SIZE(*p*) (GET(p) & ~0x7)

This little adventure was mostly just to show you that these #include statements that use system libraries are not magic, and to point out that most code will end up loading shared system libraries (.so files on Linux, .dll files on Windows)

Okay, so, that’s done. Line 2 of our 6 line hello.c is just ‘white space’ or a blank line, so we can skip it. Line 3 is where things get interesting again, with int main() {. The main() function is special, as without doing something weird, it’s where your code starts from. You may often see this line as int main(int *argc*, char const **argv*[]) too, which I’ll get to in a bit.

So, let’s break this down, starting with int.

C is a statically typed language, this means that each variable has a defined type, but also that each function has a defined type it returns and expects to be given.

so, with int main() { we’re saying the main() function will return an integer. Skipping ahead a bit, we can see this is the case, as on line 5, return(0) it does exactly that, but, why?

Let’s run our code as is (./hello), then change this return code to return(2);, recompile with gcc hello.cpp -o hello and run ./hello again.

See that little 2 ↵ in my terminal? That’s the return code, but why did it get printed?

Well, when the program exits, it returns that number to the process that called it (In this case the shell - read up on shell vs terminal in Appendix A1) and if this number is anything but 0 the shell prints it, because anything but 0 is assumed to be an error condition, and that this number may indicate what that error was. So, if we know getting to that return(0) signifies that our program ran correctly, we should, in fact, return 0.

Okay, So, other than the closing curly brace (}) on line 6 that defines the end of main, with

|

|

We only have one line left to look at, and that’s line 4, which is

|

|

Okay, breaking it up, we first see that we’re using printf() the function whose definition we imported from stdio.h and which is actually being executed from a linked system library stored in /usr/lib/libc.so.6

Okay, so, we now have almost everything, last up is just the string that we’re printing to the terminal, which is "Hello World!\n"

But what’s with that \n on the end? Well, to understand this line we’ll need our helpful friend, the ASCII table.

On most unix based systems, you can access this at any time by running man ascii

ASCII is a really old way for computers to represent text. In most modern systems it’s been replaced by unicode (which is what lets you use emojis 🤔) but the start of the much larger character space of Unicode is the same as the ASCII table anyway. Alright, so, you’ll notice some really weird characters in the ASCII table, not just the normal symbols you’d expect. The one I’d like to mention now though is at 0xA - [LINE FEED]

Line Feed, as well as some others like Bell and Carriage Return all date back to when computers were hooked up to Teletype machines - which were basically a mix of printer with a typewriter, so, naturally, there had to be some control characters to do things like tell the machine to move to the next line.

Because we like backwards comparability so very much, we still use these same codes for modern terminals, so typing \n at the end of a line is really saying “put a line feed control code here” which, to a modern system, means go to the next line.

The reason we do this is because without it, the output of our program looks like this (ran first as is, then with the \n removed)

[vega@lyrae ~]$ ./hello

Hello World!

[vega@lyrae ~]$ gcc hello.c -o hello

[vega@lyrae ~]$ ./hello

Hello World![vega@lyrae ~]$

see how it doesn’t leave room for the prompt to be printed on a new line of its own!

The ASCII table has some other interesting side effects too. See how a capital ‘A’ has an ‘index’ 32 higher than a lower case ‘a’, and the same for ‘B’ to ‘b’. Let’s use this to our advantage to make the ’d’ in ‘Hello World!" uppercase.

|

|

[vega@lyrae ~]$ gcc hello.cpp -o hello

[vega@lyrae ~]$ ./hello

Hello World!

Hello WorlD!

Hello Worlz!

Hello Worlz!?Hello Worlz!?

[vega@lyrae ~]$

Recursive Fibonacci #

The Stack™

Calculating sine and pi #

pseudocode, types

Sorting a list #

pointers, heap

mention efficiency, analysis later

https://github.com/laserallan/malloc_geiger

Palindromes #

Cipher #

Bit Operations #

|

|

0b11 in binary is 3, (the 0b prefix means binary) 1 here is the number of places we want to shift it left, so, x would now contain 0b110 which is 6.

unsigned, signed bit, 1’s compliment, 2’s compliment

Bit Twiddling Hacks from Sean Eron Anderson

System Calls #

Assembly #

I very, very much so recommend getting a feel for writing assembly with the TIS-100 game. It’s $7 on steam (at the time of writing).

Interrupt & Signal handling #

Part 2, Going Deeper #

[TODO] Interacting with the above, this program should run in the background and update the data, based on window focus events using libxdo

This program should actually provide the VAST majority of the source code, with purposeful errors for demonstrating the below

furthermore, the C code should check to see if there is a new article, and if so it should call a function that first checks a ‘meta’ entry to see if the python code to change a published time to be newer or the number of entries has changed to optimize:

-

generates a template markdown file for the article if PUBLISHED is FALSE and no file for it exists,

-

generates a template markdown file for the article if PUBLISHED is TRUE and no file for it exists,

-

generates a HTML file from the markdown if PUBLISHED is TRUE and no HTML exists then updates TEDIT, TPUB

-

remove the HTML file if PUBLISHED is FALSE and an HTML file for it exists,

however, every time this will still need checked to monitor the md for changes, using ionotify

-

generates a new HTML from the markdown if PUBLISHED is TRUE and md has changed, then updates TEDIT

-

if markdown is removed, the HTML file should be as well

What are we going to do? #

[TODO]

Tools to use #

[TODO]

Pseudocode #

[TODO]

Writing it #

[TODO]

using a code editor, header files, libraries, writing and using a Make file, stdout / stderr,

Debugging it #

So, by now you’ve written a fair amount of code, and I’m sure you’ve figured out that a bunch of tiny issues can get really annoying. Maybe you keep forgetting semicolons, maybe you wrote ‘=’ instead of ‘==’ when doing an equality check, whatever. Turns out, there’s an easier way to catch these kinds of errors and it’s available for most languages. Allow me to introduce you to…

Linting: #

Yeah, it’s literally named after the fluff you’d find in your hoodie pockets, but, it’s still a super necessary tool. A ‘Linter’ is a static analysis tool, basically it makes sure your code is good before you run it. There’s a whole bunch of linters out there. As a pretty stupid example, let’s look at this python:

Here’s our stupid simple example, here we want a program to show us the output of sin(1…10)

|

|

If we run this code anyway, we’ll see python print:

<div style="float: left; width: 30%;">

This code intentionally has a few issues stopping it from running, thankfully the Linter, in my case VSCode’s Pylance, found them both:

[5,9] : "math" is not defined

[5,18] : "x" is not defined

Here, it’s saying on Line 5, character 9, (where the word math starts) I have no function named math. Furthermore, on the same line, but character 18, the variable x is not defined. Running the program did already tell us that we didn’t have math defined, but this caught that x was undefined too. Let’s fix up the code, and add some print debugging while we’re at it.

|

|

now running our code yields this:

the value of sine( 0 ) is 0.0

the value of sine( 1 ) is 0.8414709848078965

the value of sine( 2 ) is 0.9092974268256817

the value of sine( 3 ) is 0.1411200080598672

the value of sine( 4 ) is -0.7568024953079282

the value of sine( 5 ) is -0.9589242746631385

the value of sine( 6 ) is -0.27941549819892586

the value of sine( 7 ) is 0.6569865987187891

the value of sine( 8 ) is 0.9893582466233818

the value of sine( 9 ) is 0.4121184852417566

But, remember I said we want sine(1…10)? The linter no longer has any problems listed, so what’s up? Well, that’s a limit of static analysis, it can only find errors that occur statically and it’s not able to read your mind. Here, the issue is that python’s range() function is inclusive of the first number, and not the second, so it should be range(1,11) to work correctly.

So, what can and can’t static analysis do (with some exceptions depending on language and linter):

STATIC ANALYSIS CAN:

- (Usually) tell you missed something trivial, like forgetting a semicolon at the end of a line

- (If in a strongly typed language) Tell you if you’re doing something stupid with types

int x = 10; String y = "test"; int z = x + y;would tell you to quit being a dunce

- Let you know if you’re doing something that’s bad practice

- Often code formatting, like warning you that a line is super fucking long and is why you have a tiny horizontal scroll bar.

- Warn you about unused variables

- Warn you about undeclared variables and functions

- Warn you about some math fuckups (divide by 0, integer overflows, etc.)

- Warn you about some out of bound accesses (accessing the k+1 element of an array with k elements

- Warn you if you try to dereference a null pointer

- Tell you about some dead (unreachable) code.

- find some security issues

- find some memory leaks

STATIC ANALYSIS CAN NOT:

- Read your mind - if you write an

add(a,b)function asint add(int a, int b) { return(a * b) }it won’t know you fucked up - Know what is relevant - it’s not uncommon to get a huge pile of warnings you don’t care about while doing initial development. This can make for a sea of problems that is just… exhausting

- Always be right - There are occasional false positives

- Find all issues - It’s in the name, it’s static analysis. Not Dynamic. Your code is dynamic. It runs, it lives. Static Analysis is just doing a once-over to let you know if there’s something super obviously wrong, not doing in depth diagnostics.

- Stop you from writing stupid, inefficient, insecure, and otherwise shit code.

- You want to implement the obnoxiously slow recursive version of the Fibonacci function? It won’t stop you.

[TODO], Clang Tidy, and using it in VSCode

[TODO]

gdb + gef, gdbfrontend, Valgrind, https://cdecl.org/, etc. Mention Virtual v Physical addressing/translation

https://github.com/hediet/vscode-debug-visualizer/tree/master/extension

overflows

Analyzing the Assembly #

[TODO]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce id tellus ultricies, tempor mi interdum, pulvinar orci. Proin volutpat tincidunt tellus, facilisis iaculis elit scelerisque vel. Integer auctor vulputate augue non vulputate. Duis id orci ac tortor sollicitudin semper. Sed vulputate ipsum in eros semper laoreet. Praesent justo odio, porttitor non rutrum vitae, dignissim vitae augue. Cras aliquam mi sit amet massa accumsan viverra. Sed nec malesuada libero, vel vestibulum lacus. Sed in facilisis turpis. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam quis tempus lacus. Proin fringilla bibendum erat. Nullam auctor efficitur lacinia. Donec dapibus, tellus sed porta facilisis, sem magna maximus odio, quis semper purus orci interdum velit. Nulla et maximus urna. Maecenas sed nibh in ligula rutrum fringilla.

Art by @awr_hey, Rachel the Rox belongs to @PixelatedWah

[TODO]

Cutter, TIS-100, Shenzhen IO,

Patching it #

[TODO]

source patching, binary patching

Where to get more practice with low level programming #

[TODO]

https://github.com/rby90/Project-Based-Tutorials-in-C

Fast Inverse Square Root - A Quake III Algorithm (YouTube)

Why mmap is faster than system calls (Alexandra Fedorova)

Computer Science from the Bottom Up

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pragma_once vs include guards, why they exist

https://embeddedartistry.com/blog/2019/04/08/a-general-overview-of-what-happens-before-main/