16 - Git, Testing, CI, and CD #

Testing #

@jnesselr replying to @alicegoldfuss (Nov 13, 2018)

+----------------------------------------------------+

|Me: *does major refactor* |

|Tests: ✓ |

|Me: I don't believe you |

+----------------------------------------------------+

[Suspended User]

+----------------------------------------------------+

|Me: *deliberately breaks something, just to be sure*|

|Tests: ✓ |

|Me: oh no |

+----------------------------------------------------+

@boo_radley

+----------------------------------------------------+

|Me: *changes nothing* |

|Tests: ✗ |

|Me: oh no |

+----------------------------------------------------+

[Suspended User]

+----------------------------------------------------+

|Me: *runs tests again* |

|Tests: ✔ |

|Me: oh no no no |

+----------------------------------------------------+

src: https://twitter.com/boo_radley/status/1062513898954391552

Software Testing #

unit tests, integration tests, performance testing - https://github.com/sharkdp/hyperfine

Hardware Testing #

Automated Building and Testing #

[TODO]

Fuzzing (sandsifter), make and alts, etc.

Continuous Integration #

This is a subject that many people have written books about, and in a small-to-medium sized open source project, may not seem necessary. But its usefulness will sneak up on you faster than you might think.

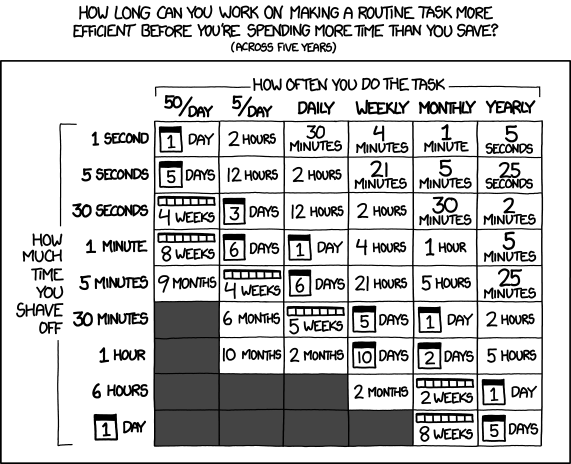

First, there is the total time savings. If you consider everything it takes to make correct and clean code – not only compiling, but linting, testing, etc – then it is definitely worth automating for yourself. And if it’s worth automating for yourself, it’s worth automating for others.

Second, there is consistency. Again, if you want all of your code to compile, you have to gate committing code to a successful compile (or at least syntax check). If you want all your code to have a certain format, then you have to gate committing code to passing lints. This will become a headache much faster than you think – even for a simple project!

Third, there is compatibility. A big part of open source is that it must be flexible, and support multiple environments. If you end up using a lot of GCC-style syntax, for example, someone with LLVM, ICC, or another compiler might have trouble building it. A CI system can test builds in many environments, not just the one you develop in.

Finally, if you start actually building out compatibility? It is a very small step to Continuous Deployment. And then you’ve got something really nice to build a community around your software.

Speaking of community, it is worth noting: if you want to impress people and make contributions, find an open source project who didn’t learn this lesson, and write or improve CI for them. This will have a long-term positive impact that the community will benefit greatly from – even if it takes a while for the payoff to be realized.

Docker: the portable way #

There are a lot of different git platforms out there, and many of them have their own CI. In addition, the most popular ones are owned by companies who have a sketchy track record in open source – or once had good ones, but then were acquired by others who did.

As a result, I want to push toward a tool that is platform independent: docker. This has some trade-offs:

- It’s independent of any CI provider

This may or may not be important to you. I would simply note that many platforms and CI systems have been taken over or bought by open-source hostile companies. Even formerly visionary ones that don’t start with G. - It’s well supported by most of them (a “command” makes it easy to handle containers)

- You can run the full CI on your own machine, e.g. to debug it without 20 pushes to trigger a rerun

- It doesn’t rely on their support for a particular OS (especially ancient or exotic ones)

- But it means you are re-inventing the wheel to some extent compared to their tooling

I’m going to presume you’re familiar with the basics of docker and have read the Containers section of the Servers chapter. This section shows you specifics for this.

In short, CI is way to build out your support matrix. Want to support Ubuntu, Debian, RedHat, and Arch Linux? Want to support every Python version from 3.2 to 3.10? Want to try compiling your C++ library with multiple compilers?

With docker, just make one container for each, and run them all! (Although for the Python version specifically, tools like the tox library can solve this in only one container.)

Let’s suppose we have a C++ project, and we want to make sure that it supports a variety of compilers. The easiest way is to define a docker file that prepares that compiler, but the actual compiler itself is not hard-coded. Instead, it is set up using ARG commands in the Dockerfile.

Here is what that might look like:

FROM ubuntu:20.04

# Default to the distro's current GCC version

ARG cc_pkgs='gcc g++'

# The name of the C compiler

ARG cc=gcc

ENV CC=$cc

# The name of the C++ compiler

ARG cxx=g++

ENV CXX=$cxx

# Install the compiler packages, along with any dependencies

# Suppose your program requires OpenGL, for example:

RUN apt update && apt install -y libopengl-dev build-essential $cc_pkgs

With this container, it should be possible to run a build by bind-mounting the source inside. This is because the variables used by GNU Makefiles, Ninja, GNU Autoconf, etc., will be set.

It is easy to make all the containers for different compilers with a single shell script:

|

|

Then you can test it on any compiler you wish.

If your CI provider supports “build matrix” definition (most do), then you don’t even need to do that! Just put matrix variables for each one (so that the line up as a group, rather than a cross product).

(Note: this is not exact for any vendor, but gives the idea.)

|

|