Chapter 4 - Getting Rooted In Linux #

We’ve been using file in /proc and /dev throughout this, but we never really looked to see what else is in there. Let’s do that.

go ahead and open up a terminal and run

|

|

Alright, I know what you’re thinking.

What. The. Actual. Fuck.

And honestly, yeah. But first, lets talk about what we just did.

Permissions #

if you run ls it normally shows you the all the folders, shortcuts, and files in a directory, except it excludes any hidden files. In linux you can make a file or folder hidden simply by naming the folder with a ‘.’ at the beginning, so naming a folder .nsfw will mark it has hidden. Hidden doesn’t really mean much though as most file managers allow you to view hidden files/folders by checking a box, and in this case, we can see hidden items by using the -a flag for ls. running man ls you’ll see the -a flag just stands for ‘all’ and does exactly what I’ve said.

further down you’ll see the ‘-l’ flag gives a “long listing format” which is an almost impressively bad description. This means that on each listing will be displayed like this:

|

|

So let’s break that up further. Linux permissions are incredibly powerful, and are set up like this

d rwx rwx rwx , the d, or lack there of, species weather a file is a directory (folder) or file.

Less commonly you may see l, c, or b, as we do here in the /dev folder.

l is the easiest to understand, it’s a link or shortcut. That’s why you’ll see an arrow pointing to where it leads at the end

c is a character special file, b is a special block file.

Finally, you may also see either p or | here for named pipes- more about that in a bit too.

There are other possibilities here two, of which you can learn about by running info ls

The vast majority of the time you will only see d for a director (folder) or - designating a file though.

Moving on to the rwx blocks, these stand for read, write, and execute respectively and each block in order states the permission of the owner of the file, those that are in the same group as the owner, and everyone else, for this reason these permissions will almost exclusively be set such that permissions are lost with each level, for example a file with

-rwxr--r-- , is a file (no d), which may be read, written, or if it is a program ran (executed), by the owner, but by anyone else in the same group as the owner or anyone else on the system may only be read.

That’s why it repeats 3 times, there’s three access levels- Owner, Group, and Everyone Else. This mostly harkens back to when Linux boxes were shared servers at a university or business that everyone would remote into. You might want a file to only be modify-able (rw-) by you, only be readable (r--) by people in a shared group (Say, other students of the same class at a University or other managers at a business, etc.), and not even readable by others (---), this would give that file a total permission string of -rw-r-----. There are other uses of groups on systems too, usually for assigning who has access to hardware, like you may find that your user is in group called ‘audio’ if you run the groups command.

So if we changed the permissions on that python file we wrote back in Chapter 2 to be this then while anyone else could see the code, they couldn’t run it without making a copy.

with that let’s skip over the number of links, as I’ve never found it particularly useful and jump to the owner and group fields. The owner of a file is a single user, usually the one who created it. The root user is often the owner of important system files, which is why we have to temporarily use root account when we do many admin actions, such as updating or installing programs using sudo.

(note, yay calls sudo automatically and you should NOT run yay with sudo)

Next is size, this is pretty self explanatory, as its just the size of the file. Directories do take some space on the disk as they have to store the bit of their own permissions, name, and so on. On this note, directories are a bit strange in regards to the ’execute’ flag that was previously mentioned. On a directory, rather than stating if a user can execute a directory (this wouldn’t make any sense!) it says weather or not a user can see what’s in the directory at all, almost like a lock on a file cabinet.

Next is the file modification time, finally followed by the items name, both of which are self explanatory.

To round this off we need to talk about how to change these permissions using chown and chmod

chown, as the name implies, changes the owner, note, you need to also have permission to change the owner, so often times this require using sudo as well.

For example running

|

|

would change both the owner and group to me, vega (assuming I exist on your system)

but what if you want to change every file in a directory?

|

|

the -R flag (Recursive) means to apply the change to every sub folder and directory

Using chmod is pretty easy too, though there are two ways to use it.

The first, which is easier to understand is with direct flags such as

|

|

The other uses the octal system to set flags. Octal has 3 bits:

| Octal | ||

|---|---|---|

| Octal | Binary | Permission |

| 0 | 000 | — |

| 1 | 001 | –x |

| 2 | 010 | -w- |

| 3 | 011 | -wx |

| 4 | 100 | r– |

| 5 | 101 | r-x |

| 6 | 110 | rw- |

| 7 | 111 | rwx |

Now, you should notice some of those options are nonsenes? being able to write to a file you can’t read? being able to execute a file you can’t read? In practice this leads to only some of these being used, but I digress to use these in chmod simply run

|

|

which would set permissions to -rwxrw-r–

Finally one last oddity. Using ls -la you’ll see two more files that are very strange one named ‘.’ and another ‘..’ ; ‘.’ is actually the current folder, as bizzare as this sounds, effectively when you run a command with ‘.’ as an argument it is replaced with the full path to the current folder. In practice this isn’t used much, but it means running something like cd . just takes you nowhere. I assure you are practical uses though. More relevant is ‘..’ which is the previous directory. so if you’re currently in /a/b/c/d and you run cd .. you’ll be taken to /a/b/c

To round this conversation off , as previously mentioned, ‘~’ represents your home directory. This usually means it expands out to /home/yourUsername which can be particualy helpful if you are say, in /dev and want to get to your documents folder you can use cd ~/Documents instead of cd /home/user/Documents

With all of that out of the way let’s finally look at /dev !

/dev, the devices folder #

Alrighty then, first, a heads up. My /dev folder will have some things yours wont. I’m on a desktop with a lot of hardware, drives, input devices, etc. And I’ve installed hundreds of programs, some of which interface with the system at a low enough level to necessitate extra files in here. For that reason some are going to be skipped over. I’ll be breaking up the output of ls /dev into a bunch of code blocks below because of how ludicrously large this output is.

|

|

‘ashmem’ is something that is on my system as a part of a project with the end goal of running android apps natively on linux called ‘anbox’ it’s still in early development, and is very difficult to run on arch

‘autofs’ is a configurable system for mounting and unmounting storage as it is used

‘binder’ is another component of ‘anbox’

‘block’ is a directory which contains numbered links to the file system blocks used previously (such as sda)

‘bsg’ is a directory with files that, again, represent your drives at a hardware level. You can open the bsg folder and run ls followed by lsscsi and compare the outputs to understand. This is practically just an artifact of older systems now.

‘btrfs-control’ is used when you have drives on the system formatted with the btrfs file system, this is a file system that is still in heavy development primarily targeted at storage arrays that are resilient to drive failures

‘bus’ is a folder which contains a folder ‘usb’ which contains folders for each usb host controller on the system, and then their devices. This is probably the first really cool one we’re hitting as you should already be able to see how the system is letting us get data directly. To show this we’ll need to have the usbutils package installed so that we can run lsusb. If you do that you should get an output like this

|

|

I’ve added ellipsis to the output to make it fit here, but you can see there that my mouse is device 002 on bus 005. If you poke around in here it should be pretty obvious how these correlate. Note, that this is just where the system puts info about the device (it’s name, etc) not where the communication with the device actually happens (usually*). That’s over in /sys which we’ll get to more in depth in a bit, but for example here I could go to /sys/bus/usb/devices/5-2 and run cat product for example to get the human readable name ‘ROCCAT Tyon Black’.

‘cdrom’ is actually a link to the new location of cdroms- sr0 , but, still, it’s use it pretty duh

‘char’ is a folder which contains links to a lot of other things in /dev for use with legacy things

‘console’ is again a legacy component and is effectively the same as tty, which is always the current terminal. to be explained more when we get to the tty’s

‘core’ a link to /proc/kcore is a direct way to read memory, used mostly for debugging

|

|

‘cpu’ is a folder which contains a character file named mircocode. If you enable msr it can also allow you to r/w model specific registers. I don’t even know what this means. You’ll never work on this directly, moving on.

‘cpu_dma_latency’ is something to do with making sure changing between power states (sleep) doesn’t take to long, otherwise the system will just refuse to do. Not used directly by anyone really

‘cuse’ is fuse for character devices, ref fuse below

‘disk’ is the way most modern things access the disk, with separate folders for by id, label, path, or uuid

‘dmmidi’ is for MIDI or Musical Instrument Digital Interface devices. I have multiple on this system.

‘dri’ contains links to your graphics cards, this is part of the direct rendering manager for video things (3D, games, etc)

‘drm_dp_aux’ each represent an output from the GPU, so think of these as the actual cables between the monitor and the computer

|

|

‘fb0’ is your framebuffer - I can’t do this justice https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/fb/framebuffer.txt, in practice you’re unlikely to ever use this, but it’s very good to know

‘fd’ is for file descriptors, which are now in /proc this is part of how the system internally handles file reads and writes

‘full’ literally just returns no space left when accessed, used to test how a program responds to a disk full error

‘fuse’ Filesystems in User Space is a system which allows for interesting virtual drives (think things like GoogleDrive) to be accessible to the native system among other things. This is a very heavily used part of the system and worth a deeper look if you’re interested

‘gpiochip’ is for general purpose input/output like with exposed pins that can be used on development board such as the raspberry pi

‘hidraw’ is for raw communication with Human Interface Devices (mouse, keyboard, gamepad) and allows for custom drivers, like those necessary for RGB backlit keyboards

|

|

‘hpet’ “High Precession Event Timer” is for internal timer-y things

‘hugepages’ - read this https://wiki.debian.org/Hugepages , these are actually pretty important as they can make a large impact on performance, especially with virtual machines

‘hwrng’ hardware random number generator, rarely used directly, often not trusted due to known faults, typically used though the soon to be mentioned ‘urandom’ interface - https://main.lv/writeup/kernel_dev_hwrng.md

‘initctl’ part of the init system, just dont touch it

‘input’ is a directory which contains links to all input devices, going to /dev/input/by-id can explicitly tell you how some devices are connected, and can be a way to extract input form devices for input in your own programs

‘kfd’ has little documentation- appears to be for AMD GPU accelerated compute

‘kmsg’ is the i/o of dmesg which itself is the main system log

‘kvm’ is the kernel virtual machine, used for running virtual machines. We’ll talk about this more much later.

’lightnvm’ use for NVMe drives

’log’ no shit, access using sudo journalctl

’loop-contol’ - http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man4/loop.4.html, effectively used to mount images or other file systems to be read as a separate block device

|

|

‘mapper’ is primarily used for LVM systems, https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/LVM, which is used for more advance disk management but comes with disadvantages in complexity and inter-OS compatibility

‘media0’ is the i/o file for a webcam

‘mem’ is direct access to the system’s physical memory. This is dangerous. There’s almost no reason to do this directly, unless you’re writing a low level driver

‘memory_bandwidth’ - as the name implies. Rarely used

‘midi’ direct access to midi devices. Documentation on dmmidi vs midi unclear

‘mqueue’ used for interprocess comunnication

’net’ contains virtual network adapters, will likely contain ’tun’ by default, used for interprocess communication in weird ways.

’network_latency’ and ’network_thoughput’ is primary used to specify current minimum necessary requirements for the network, used for power saving on wireless adapters

|

|

’null’ literally just discards anything it receives. Useful when a command outputs junk when doing things, and getting rid of the junk. ‘/dev/null’ is referred to regularly in jokes in technical circles

’nvmexxxx’ the system NVMe storage device(s), will only exist if you have an NVMe solid sate drive

‘port’ used for direct access to i/o ports. Dangerous

‘ppp’ point-to-point protocol. Similar to /net/tun - https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15845087/what-is-difference-between-dev-ppp-and-dev-net-tun

‘pps0’ pule per second provides a pulse once per second

‘psaux’ , ps provides a snapshot of currently running system processes, ps aux, where aux: ‘a’ is all user processes, ‘u’ is show user/owner, and ‘x’ processes not attached to a terminal

‘ptmx’, pseudo terminal master/slave, used for virtual terminals, like the one’s you’ve been opening in KDE

‘ptp0’ precession time protocol, links to realtime clock

‘pts’ interval virtual filesystem, used for things like docker. Works closely with ‘ptmx’

|

|

‘random’ waits for true randomness and will block things from finishing until enough entropy is generated

‘rfkill’ kills all radio transmission on system

‘rtc’ real time clock, direct access - we’ll talk more about real time clocks and time in networking.

‘sdxn’ the ’normal’ representation of block devices like HDDs, SSDs, and flash drives to the system. Each number is a partition

|

|

‘serial’ contains references to serial devices by id or path

‘sgx’ are mostly just remaps of other devices for legacy support

‘shm’ is for shared memory, to be passed between programs

‘snapshot’ is used for hirenation

‘snd’ sound devices raw access, legacy and probably will not work

‘sr0’ used for optical media

‘stderr’ is the standard error interface, try echo 1 > /dev/stderr - you should see an error return code depending on your terminal setup

‘stdin’ is the standard input interface, try echo hello | cp /dev/stdin /dev/stdout

‘stdout interface, try echo hello > /dev/stdout

|

|

TTY’s, these are important: #

’tty’ the currently active terminal, try echo 1 > /dev/tty

’ttyx’ are virtual consoles accessible though ctrl+alt+fx, where fx is a function key. You should ben on tty7 by default (maybe? if not you might have to use ctrl+alt+fx on each number until you find your graphical environment again), go ahead and try it now. Note you may need to hold the ‘fn’ key as well depending on your keyboard.

’ttyACMx’ or ’ttyUSBx’ are attached USB devices that can be accessed as a virtual terminal. This is mostly used for development boards, and we’ll be using this later

’ttySx’ are serial port terminals, rarely used outside of scientific or server gear. The physical connector usually looks similar to VGA cable. Your motherboard may well have a serial port header for adding this even if you don’t physically see one available on the outside of the case

|

|

‘udmabuf’ Uniform Direct Memory Access Buffer https://github.com/ikwzm/udmabuf, you probably don’t care

‘uhid’ for Human Interface Device stuff on the system side, you shouldn’t mess with this

‘uinput’ https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v4.12/input/uinput.html, basically you can fake a keyboard or mouse in your program

‘urandom’, the main source of random numbers. give it a shot but running head -5 /dev/urandom

‘usb’ folder which contains character devices to the HID inputs, used by the system

‘userio’ mostly used for laptop touchpad drivers

‘v41’ part of the video subsystem

‘vcsx’ virtual console memory, used when running a terminal emulator

‘vcax’ virtual console stuff

‘vcsux’ virtual console stuff

|

|

‘vfio’ is used for passing hardware directly to virtual machines, often massively improving performanec

‘vga_arbiter’ if you still have a computer that uses vga I’m sorry. This almost certainly doesn’t matter to you even if you do: https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v4.16/gpu/vgaarbiter.html

‘vhci’ used for passing though usb devices to virtual machines

‘vhost-net’ & ‘vhost-vsock’ used for virtual machine networking

‘videox’ the graphics adapter in the system. Most systems will have only one, some will have two, very, very rarely you may have more.

‘zero’ generates an infinite stream of zeros. Used for generating test files of arbitrary size, among other things.

And That’s it, congrats. Now lets go to /proc

/proc, the fake file system #

/proc doesn’t really exist, it’s a memory only system used primarily for information about processes, hence the name.

https://www.tldp.org/LDP/sag/html/proc-fs.html & https://linux.die.net/man/5/proc

Let’s dig in by hand a bit though, lets start by opening a terminal and running cd /proc

if you run ls you’ll see a bunch of numbers followed by some strange things, like uptime

let’s start with the not-number things. We’ve already seen cpuinfo and meminfo, but there’s other stuff in here too. Running cat uptime will tell us how many seconds the system has been powered on for, for example. A lot of things in here are bit hard to understand, but things like ‘uptime’ and ’loadavg’ can be legitimately useful in our own programs. running cat loadavg you’ll see some numbers that represent how much load the system is under. You can use the above links to learn more, but now we’re going to dive into the juicy bits!

Before we do so though, let’s grab a program that will make our lives a bit easier called ‘htop’, just use yay to install it.

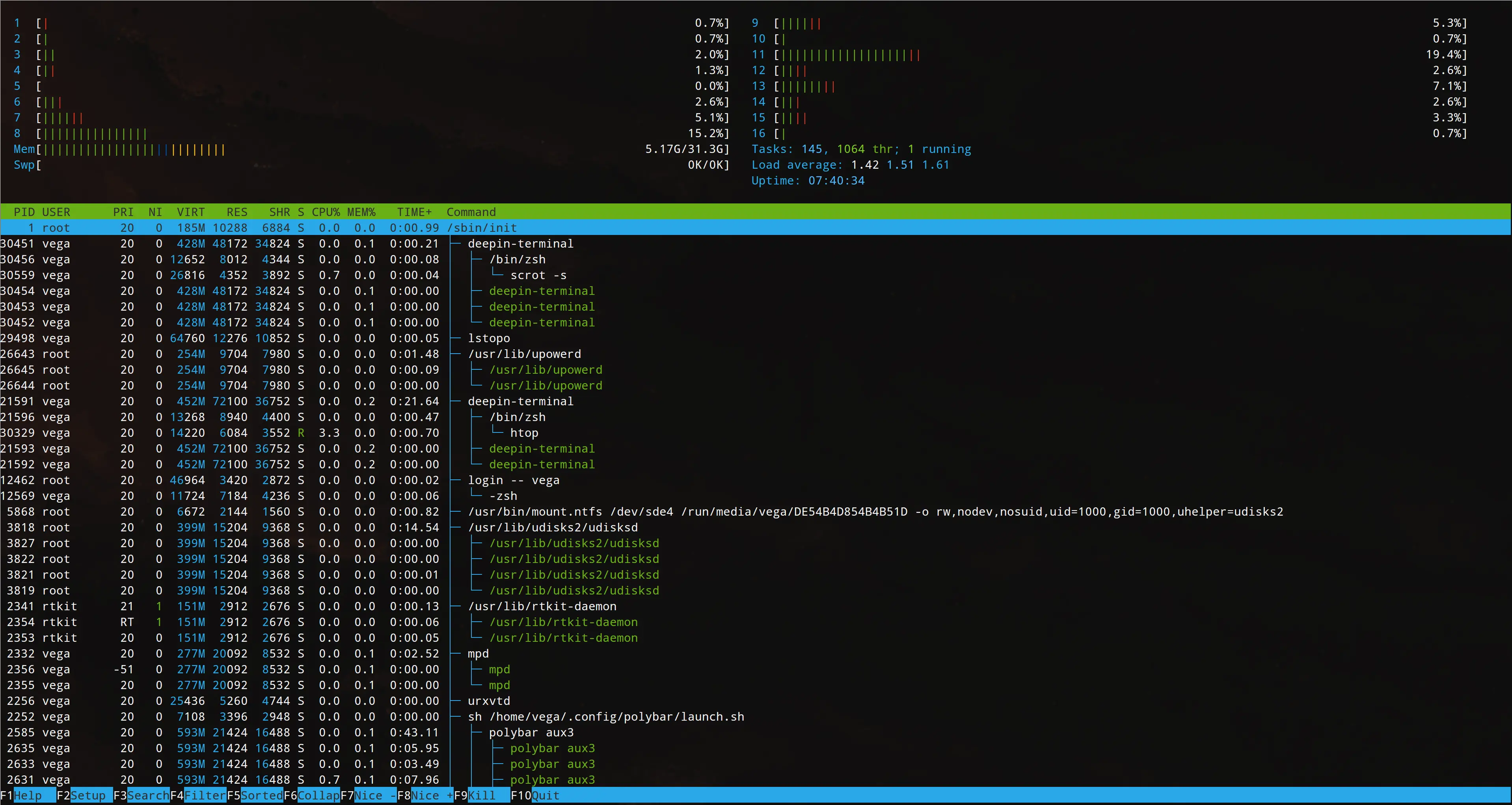

once it installs go ahead and open it up

you should see something like this:

This is a super powerful equivalent to task manager from windows. You can see the load on all 16 of my cpu threads, the memory usage on the system, uptime, loadavg, and number of tasks running here, but best of all we can see a nice tree of all the processes, and how each one of them is impacting the system. (you may need to press f5 to put it in tree mode) From here you can also see the Process’s ID known as the PID, these numbers should directly corolate with those visable in /proc

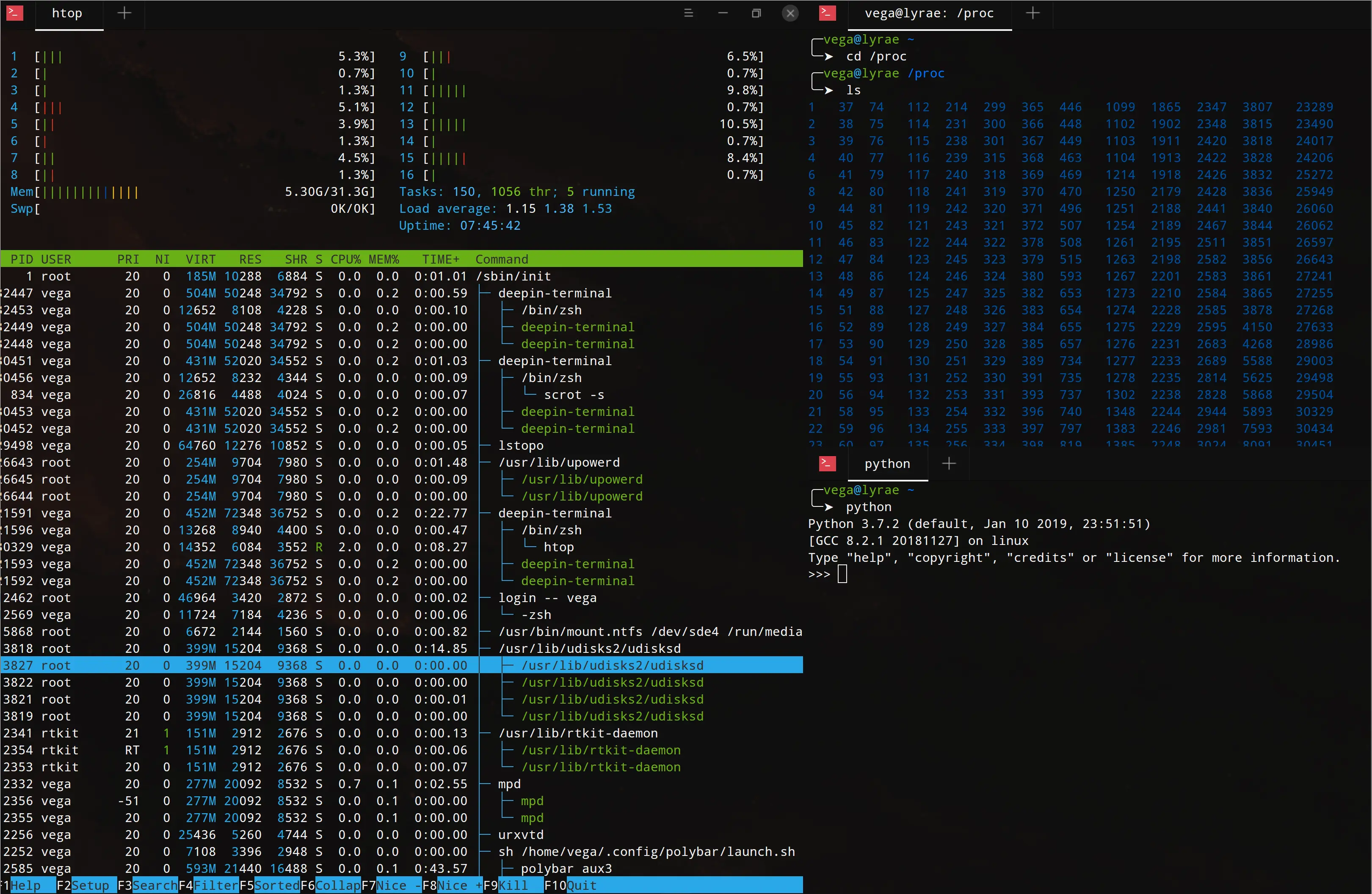

Leaving that windows open lets open up two more terminals, in one navigate to /proc and in the other start up python:

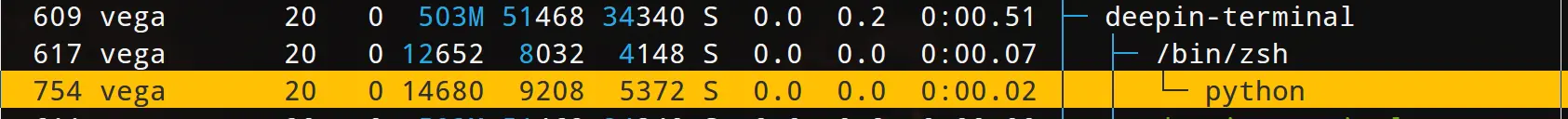

from here go back to the window running htop and use f3 to search for python if there are multiple processes that come up just keep pressing i3 until you find one that has a tree that looks like:

(note your terminal will probably be named either konsole or xterm, not deepin-terminal)

and look to the left to find the pid of the running python process, in my case it’s 754.

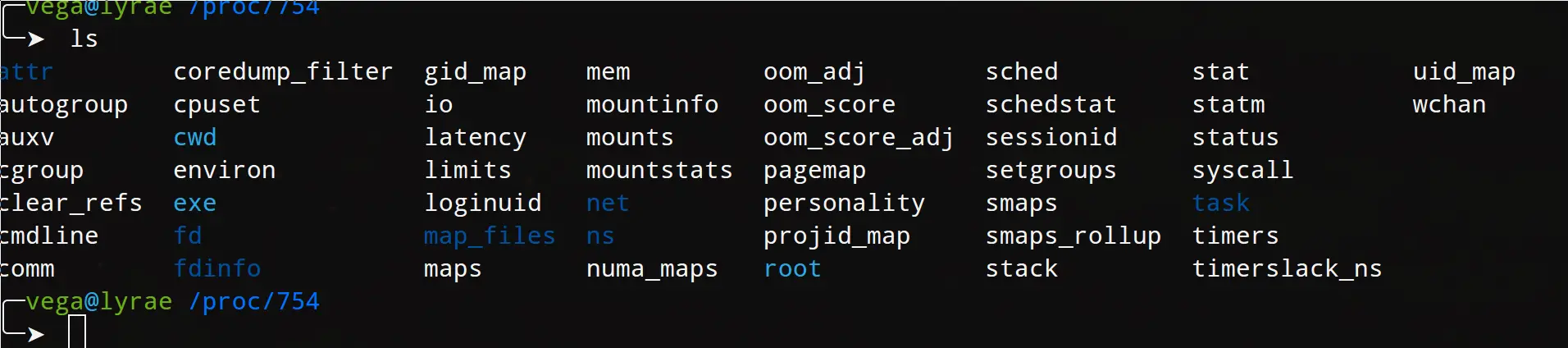

Go over to the terminal where you navigated to /proc and now navigate to the folder with the id of your process, in my case i’d run cd 754 then run ’ls’ and look at everything in this folder:

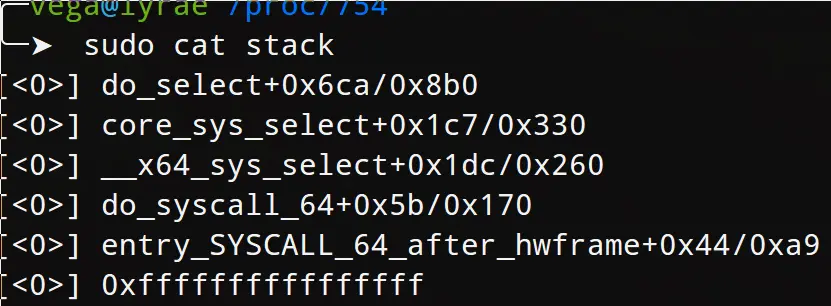

now, we’re gonna run one more thing before we leave, and we’ll come back to it later, but I want to show you now, so you can appreciate how cool it is later: go ahead and run sudo cat stack

you should see something like:

but when we run this in the python terminal:

|

|

and read the stack again we’ll see:

Which while may not look overly interesting, I assure you will be something of interest later.

One interesting processed to note in here is the process numbered ‘1’ which, if you look back in htop, you’ll see is the init process. This means it’s actually possible to look at a mountain of deails about the init process, which we’ll talk about in a bit.

Before we leave /proc, look back up at all the file that each process has and take note, also notice how some of these relate to what we saw in /dev

Take a breather,

As you can see, Linux gives us a lot of raw access to the system. There are no training wheels here. While you can use Linux the exact same way you used windows: watch YouTube videos, open a graphical file manager, etc, you can also get down to the nitty gritty of the OS.

/bin, /sbin, /lib, /lib64 #

[TODO]

symbolic links to usr explanation

/sys #

echoing to change settings, probabaly focus on device

/usr #

[TODO]

Share, man, local, var

/boot #

[TODO]

boot loaders, init, initrd fs?

/etc #

… and etc.

Literally. the etc folder contains system configuarion files mostly. Remember back when we installed and you used nano /etc/fstab that was editing the list of file systems that the system loads at boot, a configuration file. When we configure SSH later, it’s config files are stored here too. Basically, most of the admin level system config files and default config files (lower priority than the config by the user) files are here. As you learn about your system and tweak things you’ll find yourself in this folder rather often.

[TODO, add chapter links]

Some of the more interesting things in /etc are:

/ca-certificates/– we’ll talk about these more in networking [TODO]/conf.d/– various system default config files for system services/cron.d/,/cron.daily/,/cron.hourly/, etc. are all form thecroniepackage which can be installed then enabled with systemd. Note, systemd timers are a built in way to do the same thing. cron is the ‘old’ way of doing thing, but is super simple to use/crypttabis the similar to/fstabbut for encrypted partitions/cupsis a folder used bycups, which is the backend used for printers in linux/dbus-1/is used bydbuswhich is a backend for interprocess communication in linux/dconf/is a folder used bydconfwich is used to store config settings.dconfis a cli tool for changing these settings/gconf/–gconfis very similar to dconf but outdated. Still used by somethings though./dnsmasq.confis used bydnsmasq, which will be discussed in networking [TODO]/default/stores default configuration files, typically these get overriden elsewhere by the user/dhcp_fingerprint.conf,/dhcpcd.conf,/dhcpd.conf, and/ducpd6.confare all part ofdhcpcdanddhcp, used for reciveing DHCP information. This is dicussed further in the networking chapter [TODO]/dkms/framework.confis used to configuredkmsor Dynamic Kernel Module Support which is used to load modules for the kernel without building the kernel from source. In practice this means drivers for various hardware can be loaded even if it’s not in the linux source tree. Read more here: https://www.linuxjournal.com/article/6896/envriomentis a configarating file for pam_env files. Basically, enviroment variables that you want to be loaded at boot can be put here. For example to change the defalut editor used by command line programs you can setEDITOR=vimorEDITOR=nanoor whatever you like here./ethertypesis a file listing various ethernet protolcols, we’ll come back to this in the networking chapter [TODO]/exportsis used to setup NFS shares, again, in networking [TODO]/firewall.d/,/gufw/are where firewall settings are stored, dependant on the firewall progarm used/fonts/holds your fonts, go figgure. You’ll need to update the font database if you install things manually: https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Fonts#Manual_installation/foremost.confis used by theforemostpackage, it contains information about file headers, footers, and data structures for file recovery purposeses. For example, if you have a backup .img file of a failing hdd and need to scan for .jpg file headers to recover images/freeipmi/contains config files for Intelligent Platform Managment Inferface Modules. We’ll talk about this more in servers [TODO], but essentially it’s a way to, using server hardware, set BIOS settings, monitor hardware, and turn the system on/off remotely./freetds/,/mysql/,/sqlmap.conf,/odbc.ini,ODBCDataSources,andodbcinst.iniall have to do with databases and database connectivity. [TODO_Ch17]/fstab/short for file system table contains a table of file systems to be mounted at startup and options they should have. Settings here can dramatically effect fs performance or cause your system not to boot, so make sure you know what you’re doing. Even if your system doesn’t boot because of something here, you should land in an emrgancy shell where you can edit/etc/fstaband fix the mistake/fuse.confis the config file forfuse, which is dicussed below in file systems./gdb/gdbinit– you probably want to put the global gdb config file at~/.gdbinitnot here in /etc.gdbis discussed more in debugging [TODO_Ch18]/groupis where linux user groups are defined. You probably want to use thegroups,groupadd,groupdel,groupmems, andgroupmodcommands./grub.d/contains config files and boot loader entries for the grub bootloader. Not relevent if you’re using systemd boot on a UEFI system/gshadowcontains encrypted passwords for each group.!!and!both indicated no password, though!!is no password has been set before/healthd.confused to notify if hardware has an issue (temp, fan, etc) – provided bylmsensors/host.conf&/resolv.confare used for resolver configuration. More in networking [TODO]/hostslocal host configuration file. Very useful, in networking again [TODO]/httpd/, and specifically/httpd/conf/httpd.confis used to conigure a local web server like Apache. Refrenced in Networking [TODO] and Servers [TODO]

/home, /mnt, /run #

[TODO]

discuss systemd taking over home soon

/tmp #

Users and Groups #

[TODO]

permissions discussed eariler, recap here

Drivers & Kernel Modules #

Art by @monoxromatik, made for @Freixfox

[TODO]

udev rules

File systems #

[TODO]

Inodes, Raid, fuse, ext4, ntfs, zfs, tmpfs, fat/fat32/exfat, …

include bit about named pipes

mknod

https://wiki.maemo.org/Modifying_the_root_image

Processes and Memory #

[TODO]

loading libs, forks, env variables, process ownership

lsof, strace, ltrace, nice levels - sysdig

System Calls #

[TODO]

https://github.com/microsoft/ProcMon-for-Linux

start with a syscall table

Kernel Parameters #

[TODO]

modprobe

SystemD and alternatives #

[TODO]

init system: https://www.lifewire.com/how-to-use-the-init-command-in-linux-4066930

Schedulers #

[TODO]

+real time kernel/preemption

Dbus #

[TODO]

We’ll explore more of the OS later, but for now I think the information overload is a bit much anyway, so lets move away from screens and into the world of hardware