5 - Storage #

Permanent storage is rapidly evolving, but the old guard: hard drives and tape storage aren’t going anywhere either. But why use one over the other? How do you interact with them in Linux?

[TODO] mention HDD, SSD, SATA, NVMe, usb-storage, SD, SCSI, u.2, m.2, tape, floppy, zip

hdparm

HDDs #

Hard Disk Drives or ‘HDDs’ are sometimes called “spinning rust” because unlike other modern storage devices, they’re fundamentally mechanical.

Looking at the de-lidded hard drive, you’ll see they’re pretty simple in their basic construction: a magnetized needle(s) move across (a) platter(s) and flip bits accordingly. These platters typically spin at 5400 or 7200 RPM, with the faster meaning data can be read and written faster as well. Hard drives generally are not used for speed, though, as compared to other alternatives they’re extraordinarily slow. Often, you’ll hear them called “spinning rust” now, making fun of how antiquated the idea of mechanical storage seems in the first place.

HDDs generally run at ‘good enough’ speeds for most things- like storing video, music, etc. while being much less expensive than solid state options for a given amount of storage, and with a proven reliability and without suffering from data loss when left without power for long periods of time. That said, just like any storage medium, over time data can be corrupted, so backups are still a must.

When a Hard drive is powered off, the head will typically ‘park’ off the platter (this is part of why the delidded plater above died, as it parked incorrectly) and transportation should be pretty safe, however, when running and spinning quickly they’re pretty fragile, and this is why so many older laptops have dead drives: the gyroscopic effects of spinning something that fast make it resistant to a change in orientation, causing things to scrape, scratch, or otherwise go wrong. Thankfully, most 2.5" hard drives have been hardened against this now; however, it’s still a good idea to store and run hard drives with as much protection from vibration and shock as possible. In fact, yelling at a hard drive ![]() has been shown to hurt performance.

has been shown to hurt performance.

At the end of the day, for bulk media storage that you still want to be able to access quickly or for backups, hard drives are still one of the best options.

Most hard drives connect though either SATA or SAS, with almost all consumer drives being SATA, and enterprise drives using a mix. SAS has some extra features and depending on the drive may be capable of writing and reading at the same time, a nifty trick SATA drives can’t do without alternating between the two rapidly.

For bulk storage servers, you can get insane capacities, and building one yourself isn’t all that hard. Here’s mine:

A modified powervault MD1000 with a hard drive poking out and the computer - being used an archive server - it connects to. It currently is only housing three, 3Tb SAS hard drives.

For working with hard drives in Linux, your best friend is hdparm lets use it to look at some disks. First we need to pick a disk to look at, running lsblk you should be able to see all the disks on your system, and I’ll be looking at my main data drive which is a 3.7Tb drive on /dev/sdg

The first thing we should do is get an idea about the disk usage, to do that I’ll go to the mount point of the disk on my system ( it’s mounted at /run/media/vega/raid despite the fact it’s no longer in a raid array, we’ll come back to this)

so first I’ll run df -h , that -h on most Linux commands means to make the output human-readable, printing things in terms of Gigabytes or Terabytes etc. instead of just a raw byte count.

|

|

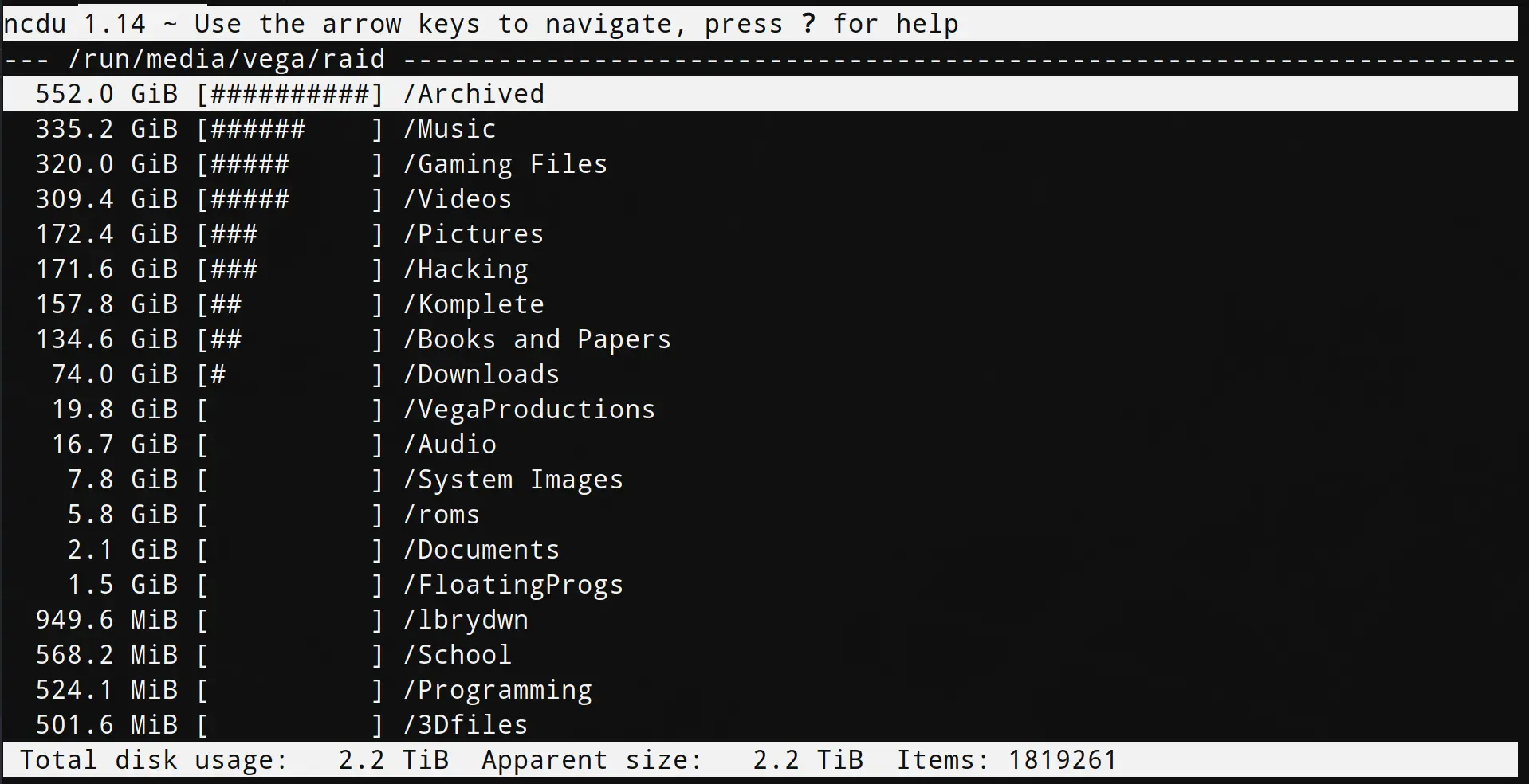

Alright, so I already have the disk 62% used, let’s give that a closer look by firing up ncdu at the mount point. This will take a little while to scan, the more files the longer it will take. After spending a few minutes to analyze the disk, I’m greeted with this:

From this you should be able to plainly see that the majority of the hard drive is taken up by Archived files, Music, Games, Videos, and Pictures. Pretty Mundane, but I could easily dive into the Archives and see why they’re so big and save myself some space

None of this is really all that interesting, though, so what about speed? How fast or slow is the hard drive? Now is where hdparm comes in. Reading the man page you’ll find the -T and -t flags both perform disk read benchmarks, one cached reads, the other raw, so let’s run sudo hdparm -Tt /dev/sdg

This gives:

|

|

You should immediately notice that cached reads are absolutely insanely high compared to buffered, in reality it’s because it was using RAM for cache, and RAM really is that fast. The reads of bulk data on the other hand? A little under 200MB/sec is actually quite fast for a hard drive. Anything between 1-200 is normal. You’ll soon see that compared to SSDs, though, this is kind of disappointing.

But, moving on, another few interesting flags available in hdparm are -g which displays the “geometry” of the drive: cylinders, heads, sectors, etc., -H for temperature.

This begs the obvious question: what are cylinders, heads, and sectors

[TODO]

Another thing of note is S.M.A.R.T tests, while not exclusive to hard drives, they’re particularly useful for them as most hard drives give a lot of warning signs before failing out right. In order to get in-depth S.M.A.R.T info on your drive, you’ll likely need to run a test first, after which you can view the results. To do this on Linux, you can run

|

|

Hard drives, being the last remaining mechanical part in a computer (aside from fans or liquid cooling pumps) are also pretty prone to failure. If you want to avoid this keep vibrations to a minimum, look for disks that are rated for your use case (being on 24/7, being next to many other hard drives, etc.) and check the drive’s MTBF or Mean Time Between Failure. You want this number to be as high as possible, often something like 1,000,000 hours.

Finally, a quick note about Western Digital Green drives: Linux eats them. Thankfully, you can use hdparm to fix this. From the man page:

-J Get/set the Western Digital (WD) Green Drive’s “idle3” timeout value. This timeout controls how often the drive parks its heads and enters a low power consumption state. The factory default is eight (8) seconds, which is a very poor choice for use with Linux. Leaving it at the default will result in hundreds of thousands of head load/un‐ load cycles in a very short period of time. The drive mechanism is only rated for 300,000 to 1,000,000 cycles, so leaving it at the default could result in premature failure not to mention the performance impact of the drive often having to wake-up before doing routine I/O. WD supply a WDIDLE3.EXE DOS utility for tweaking this setting, and you should use that program instead of hdparm if at all possible. The reverse-engineered implementation in hdparm is not as complete as the original official program, even though it does seem to work on at a least a few drives. A full power cycle is required for any change in setting to take effect, regardless of which program is used to tweak things. A setting of 30 seconds is recommended for Linux use. Permitted values are from 8 to 12 seconds, and from 30 to 300 seconds in 30-second increments. Specify a value of zero (0) to disable the WD idle3 timer completely (NOT RECOMMENDED!).

Western Digital is trying to redefine the word “RPM” (arstechnica)

![]() What Is ZFS?: A Brief Primer (Level1Linux)

What Is ZFS?: A Brief Primer (Level1Linux)

Non-Posix File Systems (Göran Weinholt’s Blog)

SSD #

Solid state drives, like HDDs, come in many capacities, speeds, and form factors; however, SSDs come in many, many more than HDDs. The primary two of note at the moment are SATA SSDs and NVMe SSDs. SATA SSDs are typically the same size and shape (though sometimes a bit thinner) as the normal 2.5" laptop hard drive; however, some other standards are used such as mSATA (about a half-credit card) and m.2 (a bit bigger than a stick of gum). Unfortunately, the m.2 spec is slightly confusing, with some drives being SATA based and some being NVMe based, and the m.2 slot itself supporting any mix (just SATA, just NVMe, or both), so when getting a drive you need to be careful that your motherboard’s m.2 slot and the drive are compatible.

The main reason you’d want to use NVMe is that it’s much, much faster. NVMe drives are often many times faster than their SATA equivalents (usually because SATA is limited to 600MB/s tops), and as of the time of writing, only slightly more expensive, albeit not supported on all systems. Do keep in mind though that NVMe drives will use some of your limited PCI-e lanes, so if you want to add a lot of expansion cards like a GPU, sound card, extra USB ports, etc. you’ll need to be careful about that.

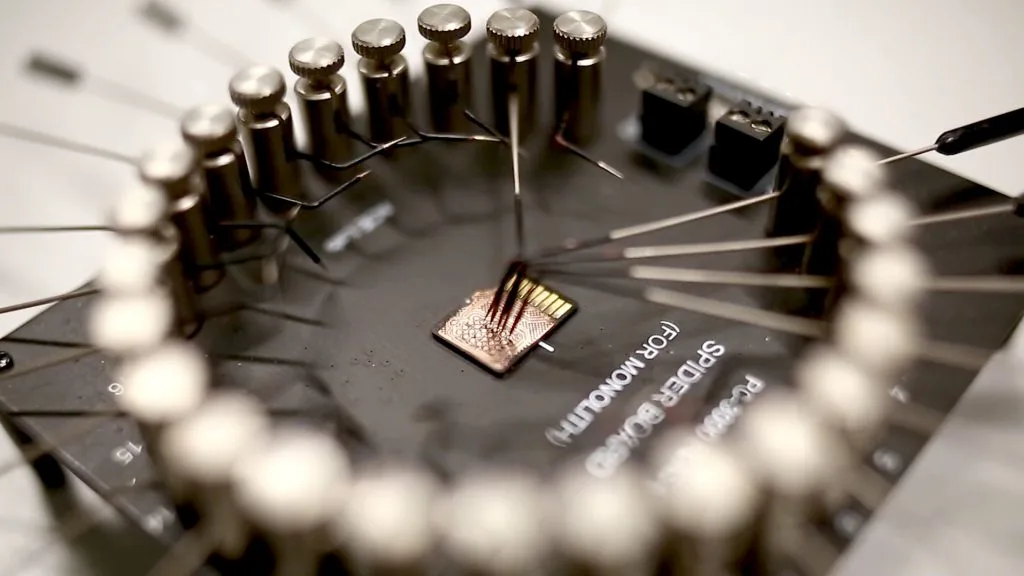

All SSDs, regardless of type, consist of 3 main parts: The Controller, the NAND, and, if they’re not garbage, some RAM. (Seriously, don’t buy a DRAM-less SSD)

All three of these can make a difference to both performance and reliability, though honestly, this is one situation where just sticking name brand is probably the best way to ensure you don’t get boned. Samsung, Intel, Silicon Power, Kingston, Crucial, Western Digital, SanDisk, Micro, ADATA, and Toshiba should all be safe bets. It’s really not worth saving a buck on a no-name brand when your data is at stake.

If you do care about the nerdy nitty-gritty, you should read about 𝐖 Multi Level Cell Flash, with the general takeaway that more levels means more space but worse speeds and durability.

It’s also worth mentioning that new flash types, controllers, and methods to make things even faster keep coming out. One of the most interesting is Intel’s Optane SSDs which use 3D XPoint, which, is fast, very low latency, and more durable than flash, but more expensive. It’s actually fast enough that in some exotic systems, it’s starting ![]() to be used as an alternative to RAM that can also keep its data though a reboot (unlike normal RAM).

to be used as an alternative to RAM that can also keep its data though a reboot (unlike normal RAM).

![]() Recovering File Systems from NAND Flash (Defcon 28)

Recovering File Systems from NAND Flash (Defcon 28)

Cloud Storage (Someone else’s drives) #

This is an opinionated guide, so now that’s about to show: Don’t do it. All cloud storage is someone else’s disks. If you want to use it as a backup sure, but I don’t see why- it’s much less expensive to just back up the reallly important stuff to a hosted server continually and periodically (weekly, monthly, whatever) backup to some external disks that you keep somewhere else. Not to mention the privacy concerns. Like, really? You want to put allllll your family pictures under the all seeing eyes of Google or Microsoft. Nah. I’ll pass.

If you reallllly insist, then check out https://www.backblaze.com/cloud-backup.html (I’m not affiliated in any way, nor do I use the service) as it’s probably the safest option, and they have good recovery options, like sending you a physical hard drive with your data on it.

But, seriously, only use cloud for a backup if you have to and never ever ever ever ever use it as a primary storage medium.

The cloud is not your friend.

Portable #

Most fixed disk enclosures (Think your normal, off the shelf portable driver) suck, albeit they can be less expensive. I’d recommend getting a portable multi-drive enclosure that runs over whatever the fastest connection you have is (Thunderbolt, USB 3.1, etc.). You can even get USB->NVMe adapters, albeit they have a nasty amount of bandwidth limiting.

Most off-the-shelf flash drives have ass cooling and will over-heat themselves to death when you use them for things like installing operating systems regularly, so I recommend just getting a bulk pack of cheap, low capacity ones to toss when they finally kick the bucket and a few nice USB->SATA or USB->NVMe adapter for your main portable storage needs. Failing that, you can always use your phone if you’ve got a nice high capacity SD card in it or plenty of spare internal storage. The problem with that is MTP or ‘Media Transfer Protocol’ is a buggy, slow mess, and there’s no other clean way to transfer things from a phone. So ¯\(ツ)/¯

Source: blog.acelab.eu.com

You might also want to look into Hard Drive Shucking if you’re in need of as much storage as you can get your grubby lil’ r/DataHoarder hands onto.

The Past #

Floppy, Zip Disks, and Tape? Really? Yes. And yes, they’re still used, so you should probably know at least a little about them.

[TODO]

Floppy, Zip, tape

RAID and Disk Pools #

Adventures in Motherboard Raid (it’s bad) - (Level1Techs, YouTube)

[TODO]

ZFS, hardware raid, software raid, emulated hardware (bios), etc.