2 - RAM #

This is RAM or Random Access Memory. The above two sticks are the normal-sized used in desktop PCs, this form factor is called a DIMM (Dual In-Line Memory Module) while the bottom two are from laptops and are called SO-DIMMS, the placement of the notch is an indicator of the generation of RAM, with nearly all modern ram being a consecutive generation of the DDR standard. At the time of writing (Q2,2019) DDR4 is common in new, medium to high-end devices, with many DDR3 devices still being used. Of note, many more compact devices solder the ram chips directly to the board, meaning there is no form factor to consider.

Just like the CPU, RAM has a speed at which it operates as well, Typically it’s listed in MHz still, but speeds range from ~1.8Ghz to ~3.8Ghz at the time of writing, dependent DDR3 or 4. While DDR4 has faster clock speeds, it does typically have a higher overall latency, meaning there’s a longer delay between when data is requested to when it’s delivered, albeit at a much higher total throughput. This is a massive topic in of itself, yet is also pretty niche as outside some pretty specialized applications RAM speed and latency has a relatively minor impact, though faster is typically better.

Okay, let’s move on to ram in Linux.

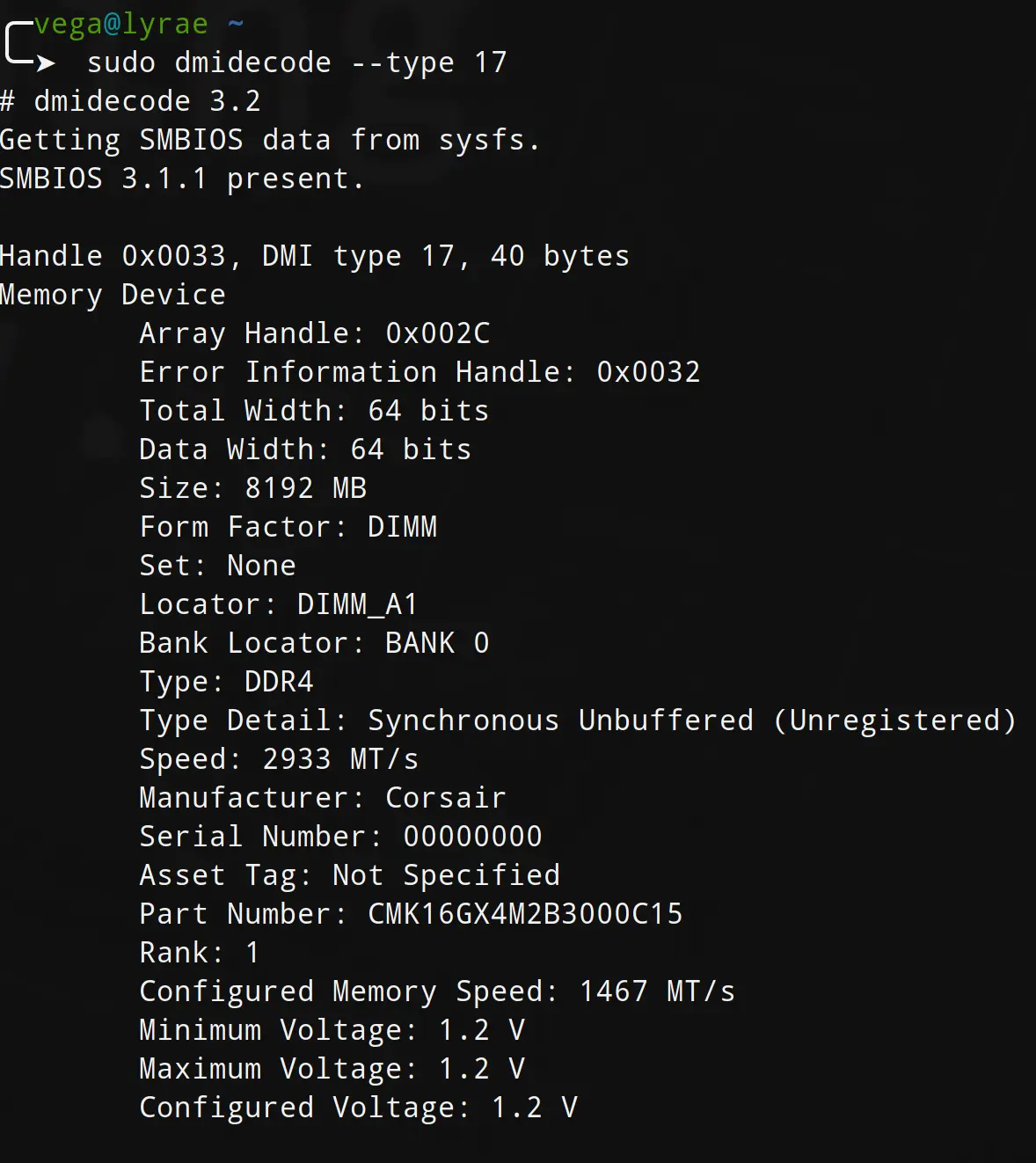

While support for this will vary depending on your motherboard, you should be able to see information about your ram by running sudo dmidecode --type 17

The output will probably repeat multiple times, printing once for each physical stick of ram in your system. I actually have 4 sticks, but I’ll just be showing one:

You should note that many of the things mentioned above can be seen here, though I do want to look at some things here.

First, size. This is an 8Gb or 8192Mb stick of ram. Obviously, the more ram the better, but you may find strange ram configurations where there’s a mix of ram sizes in a system. This can be bad for performance, though, because of memory channels.

Most modern systems use 2 or 3 memory channels, to simplify a bit, it makes it so two sticks of ram can have their speed be used in parallel. Think about it like a parking lot, if you have a total of 4 parking lots you could, theoretically, hook them all up in a straight line with one entrance/exit shared among them. This would be pretty stupid, though, as it would severely bottleneck traffic going though. Instead, you may want to add a separate entrance and exit for each, but that quickly becomes expensive. Instead, most systems use a mix of the two, connecting a pair of sticks together, allowing for added capacity, but allowing for multiple pairs to be inserted independently. A lot of people don’t fully fill all the available memory slots on their motherboard though, so instead of having 4 lots with 2 entrances you should be able to have 2 and 2, unless you mistakenly put the sticks in wrong, leaving one ’entrance’ closed entirely while the other now has a ton of capacity. On my motherboard these ’lots’ are labeled A1, A2, B1, and B2. Looking above, you can see the stick we’re looking at here is the A1 lot. It’s because of this that you should ideally have a multiple of as many sticks of ram as you do memory channels. For example, if you have a two channel motherboard and CPU then you want either 2, 4, or 8 sticks of ram. Most motherboards top out at 4 sticks, though, with 2 channel and 2 sticks being the most common configuration.

Next, I want to look at the line that says ‘Type Detail: Synchronous Unbuffered (Unregistered)’ this is referencing another type of ram, which is buffered and error correcting (ECC) memory. I’ll come back to this.

I also want to point out the voltage. Much like a CPU, the voltage a Ram module runs at is important, and needs to be kept very stable. However, it may need bumped up if the RAM is running at a particularly high speed or if it’s set higher than factory (overclocked).

Some RAM actually includes a special memory profile, often called XMPP, which can be applied in the BIOS/UEFI settings to make sure you’re getting the absolute best performance out of your RAM before manual overclocking. This may actually overclock your CPU a bit as well as a bit of a side effect.

There’s a program on your system called free which can be used to see how much RAM you have, how much is in use, etc. Let’s run free with the -h flag so we can see the amounts with nice units.

|

|

You can see I have 32Gb of RAM total (it gets truncated to 31 because it’s actually like 31.99, units are weird), with only 4.5Gb used. Most people complain about Chrome eating all their RAM, but the truth is unused RAM is wasted RAM. The OS will manage RAM for you, and if you run out start using swap (that partition we made earlier).

Let’s take a deeper dive, reading the man page for free with man free we can see it uses information from /proc/meminfo, so let’s look at that file ourselves using cat /proc/meminfo.

One of the most interesting things to point out here is the concept of Dirty memory.

‘Dirty’ memory is the amount of information that has been modified in memory, but that has not been saved back onto the permanent storage (SSD/HDD). If you were to suddenly lose power, this information would be lost.

Pagefaults and misses are also important. Because these topics are a bit hard to summarize, I’m going to recommend you read the Wikipedia page on Pagefaults and on Cache Misses. It’s okay if you don’t understand everything you’re reading. Hopefully as you read more later and gain more experience, the terms you didn’t know will ‘click’ and you’ll understand.

Going back to when cache was mentioned, though, RAM’s primary job is to hold bulk information that’s in use a bit closer to the CPU. For example, if you load a large image file it’ll first get copied to ram and then be processed though cache in chunks, this is because there just simply isn’t enough cache on the CPU to hold a large image.

Memory Density #

Virtual Memory & Swap #

[TODO] see chapters 12-24 of https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/

So, there’s a bit of complexity between how programs see memory and what is actually available going on that is really important to understand. You see, in ye olden days, computers were simple- you’d have a big ol’ pool of available memory and each program would just be told “You get the memory between ADDRESS1 and ADDRESS2” but there wasn’t actually anything checking to make sure this was upheld. If one program wanted to maliciously read another’s memory values, it could! If a program decided “You know what, I think I need more memory than this!” it could just go right out of it’s allotted space and overwrite the memory of another process. Further, it was really awkward to handle the problem of a process, halfway though running, requesting more or less memory be allocated to it, as dealing with non-contiguous regions of memory would be awkward.

Enter Virtual memory

Each program is now given a virtual address and virtual pages of memory. These pages are mapped to physical memory by using the Memory Management Unit or MMU in the processor in conjunction with the OS coordinating what process gets what memory allocated to it. Put very basically, each process is essentially given what looks to it to be access to the real, physical memory, say, the process is told “You have access to address 0x000A to 0x000C” but the operating system and MMU know that, in reality, that the memory is actually, physically, in two segments, 0xF32C to 0xF32D and 0x3D2A and 0x3D2B. The program has no idea about this mapping, and no idea that the memory isn’t actually contiguous.

This has another benefit- we can actually allocate more memory than we really have. Say we’re working on a system with limited RAM, like the Raspberry Pi 3B+ with only 1GB to go around. The operating system is going to need some of that to do its duties, says 200Mb, and then say you open two programs- LibreOffice Writer (a word processor) and Firefox, each of which needs 500Mb of memory. That’s already 1200Mb of memory, more than the 1024Mb in the 1Gb of physical memory the Pi has! So, what happens? Well, the system will start Swapping memory to disk (in this case the SD card) this means that whatever the OS deems what you haven’t used in the longest or that you’re least likely to use again soon gets taken out of RAM and is instead written to your long term storage (SD card here, but normally an SSD or HDD in a bigger computer) this is good because it means you can run more programs than you really have the RAM for, but bad because this secondary storage is glacially slow compared to the speed of RAM, so when you do actually need that information, it will take a long time to work its way to the processor. If we continually end up swapping memory from disk and physical memory, this is called Thrashing, and it is extremely bad. Even when the system isn’t being thrashed, the hiccup from swapping is often very noticeable to the user, so you really don’t want to run out of RAM.

Faults & The Dirty Bit #

Alright, so,

Locality #

[TODO] Temporal & Spacial Locality

Pages #

[TODO] What a page is, page faults. Not going into depth on Page replacement algos but at least enough to get the gist.

[TODO] Huge Pages, ref this

Memory issues, ECC, and Memtest86 #

Memory can have quite a few issues, sometimes resulting in random Blue Screen of Death (BSoD) or Linux Kernel Panics, other times just occasionally corrupting data with no way to know.

If you’re working with super critical data, you can at least know that something has gone wrong by using Error Correction Code (ECC) memory. In an ideal world, ECC would just be standard on everything. Unfortunately, Intel is a bag of dicks and uses it for product segmentation and people are cheap: ECC is also more expensive because it requires an extra bit for every byte. This also means that instead of the normal 8 memory dies per stick of RAM, ECC memory actually has 9 dies (usually). The reason there are normally 8 dies is simple- there are 8 bits in a byte. Servers don’t work on some magic 9-bit in a byte system, instead, this extra bit per byte is used to ensure the data hasn’t been corrupted.

The math to do this is generally capable of detecting and fixing a single bit flip per byte, and at least detecting a double flip.

This video explains how that works if you’re interested:

It is worth noting that along with being more expensive, ECC is also usually a tad slower. There’s also such thing as Registered/Buffered memory, which you may see with ECC as well. Buffered memory is basically just adding an extra ‘buffer’ between the read/write and again, it’s a server thing- you’re unlikely to ever see it on a consumer platform. Just know that if you’re buying RAM for a server, you may need to be careful to ensure you’re getting the right thing.

When DDR5 comes along, ECC is built into the spec for all levels to some extent because as memory speeds have increased, the likelihood of an error has as well. It’s becoming necessary for basic functionality at DDR5 speeds.

Now, ECC would be great and all, but the memory in the system you’re reading this on almost certainly isn’t using it, so what can you do?

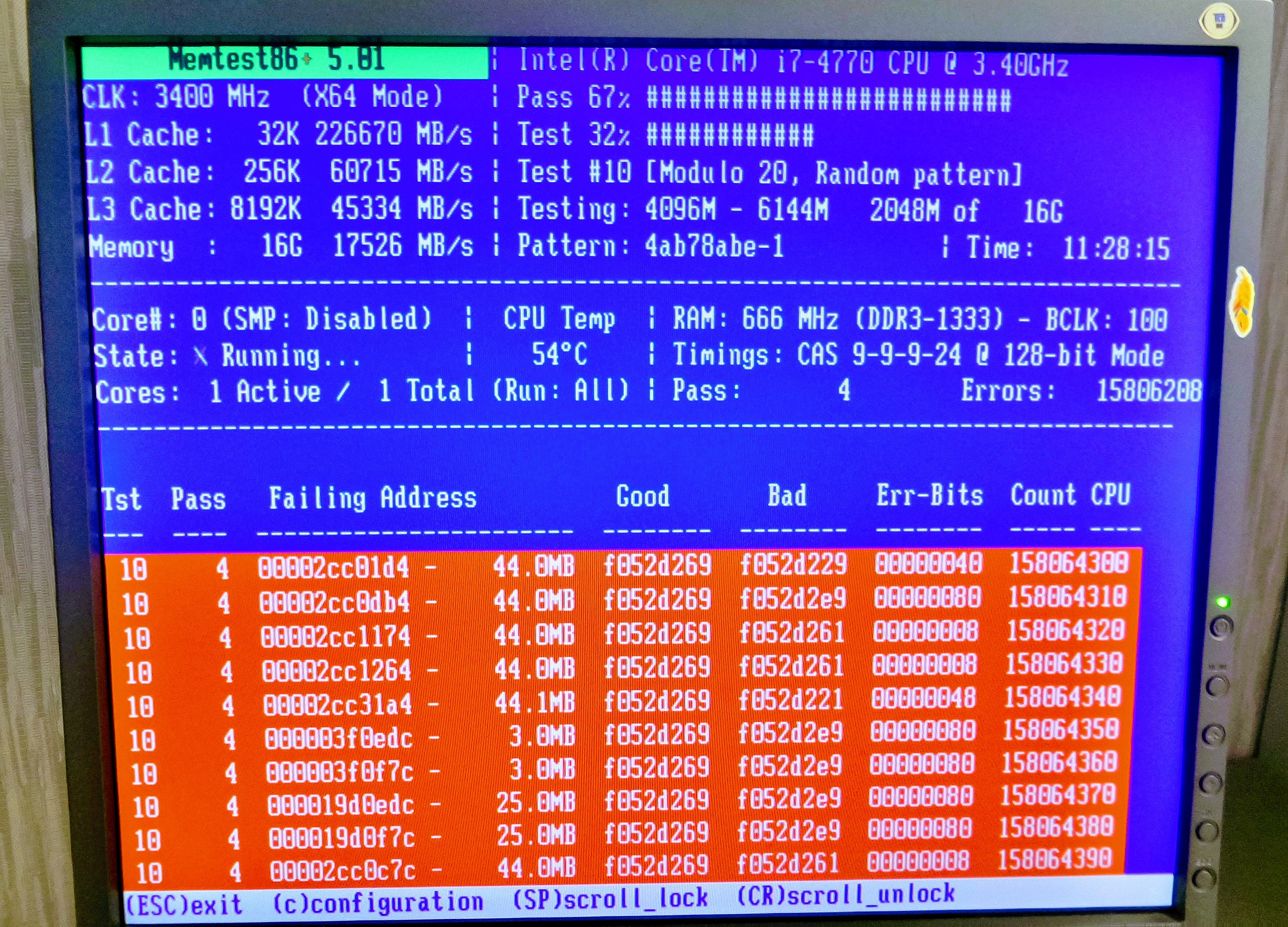

Well, for one, you need to get a feel for when something might be a memory error. Generally, if you see issues that you can’t attribute to anything in software, where there’s no obvious pattern, it’s a good bet that it’s memory. Assuming you’re on an x86(_64) system, like most laptops or desktops, you can check with 𝐖 Memtest86(+). It often needs to run for a few hours to find anything, but when it does you’ll get a big red error.

Unfortunately, this probably means you need to buy new RAM. In the absolute worst case, maybe a new CPU if the memory controller has gotten damaged, but this is unlikely.

Image by Андрей Крижановский on Wikipedia, Public Domain

You’re far more likely to get RAM errors if you Overclock your RAM as well, so just be smart if you do OC your RAM- though I really don’t recommend doing so beyond applying the XMP profile (Tom’s Hardware) your RAM may have shipped with.

The Future of RAM #

It may seem like RAM is simple enough as to not really have any opportunities for massive changes in the future. This is not the case. Currently, there are real, commercially available products implementing both Processing In Memory (PIM) and memory persistence (non-volatile main memory)

This article, In-Memory Processing by UPMEM, from AnandTech goes into the former, while the Intel Optane Persistent Memory article from StorageReview and ![]() this video from Linus Tech Tips cover the latter.

this video from Linus Tech Tips cover the latter.

It’s also very likely we’ll see new form factors as we run into problems with signal integrity. We’re already seeing the start of this with laptop’s (![]() CAMM Memory (Linus Tech Tips)) but given the signal integrity woes at hand and the rapid progress of stacking silicon in recent years, it’s not even out of the question we’ll see it be on a silicon interposer soon- RIP upgradability, but hello speed.

CAMM Memory (Linus Tech Tips)) but given the signal integrity woes at hand and the rapid progress of stacking silicon in recent years, it’s not even out of the question we’ll see it be on a silicon interposer soon- RIP upgradability, but hello speed.

Row Hammer #

Row Hammer is vulnerability that arises due to the way memory is arranged physically and electrically on a memory stick. It lets you flip bits you shouldn’t be able to by ‘hammering’ on the row above or below the target row, hoping that you can induce a bit flip in the target row. It’s also been “fixed” multiple times, and is still a problem …though it is supposed to be fixed for real this time in DDR5

𝐖 Row Hammer’s Wikipedia Page has some a very good overview as well as some example assembly to explain the exploit