4 - Graphics & Acceleration #

Photo by Thomas Foster, depicting an Nvidia RTX 3070

Hi Gamers!

This page will obviously appeal to you, those that drive the sales of these chonky, expensive cards; however, it’s important to note that this page is about all graphics & acceleration- from the iGPU in low power systems to the compute cards used for AI research and wasteful crypto mining. Still, this more in depth knowledge will probably be helpful in helping you extract more FPS from your GPU.

Hi Miners, Please Stop!

Yes, I realize this page may be helpful for educating those that wish to mine cryptocurrency. The best I can do is express my incredible distaste for the practice. It’s a massive waste of electricity for what is mostly used either as a pyramid scheme or for criminal activity - and I’m even saying this as someone who was given free crypto and made a few bucks on it. See Cryptocurrency is an abject disaster (Drew DeValut’s Blog), This Twitter Thread from @ummjackson, this one from @Pinboard, or This video … I could keep going. If reading these, and looking at their sources, doesn’t convince you, then you’re obviously so biased as to not consider the arguments fairly. Yes, I see why crypto is cool, and I see its use as governments become increasingly interested in spy tech, etc. This isn’t the solution, and anyone that can separate their morals from their wallet can see that.

Most ‘beefier’ systems have a graphics card, but (almost) every computer that can output a video signal has dedicated graphics processing of some sort. For many lower end or low power systems (especially laptops) this graphics processing unit, or GPU, is built into the CPU and uses the system’s same ram for video. For larger systems there’s typically a larger graphics card (often the graphics card is called a GPU as shorthand; however, the GPU is technically just the processor on the board), which is a separate device hooked up though an expansion connection (like PCIe). Typically, these cards differ from their integrated-into-the-CPU counterparts in that they’re much, much faster and drink much more power. In general the GPU is required because while CPUs are great at very fast consecutive operations like taking ‘1+1=a, a+1=b, b+1=c’ the GPU is excellent at parallel operations like ‘1+1=a, 2+2=b, a+b=c’, where both of the first two operations can be done at the same time by different processing units before being manipulated together in the third operation. In reality, this is because the modern GPU really only treats pushing color data to the screen as a secondary operation, instead its main purpose is to do complex matrix and vector math which is what goes into drawing polygons in a 3D scene, and these matrix operations are massively parallel. So while a CPU has at the high end a dozen cores, a GPU may have multiple thousand. These cores are much more limited in what they can do of course, and typically run at a lower clock speed than the CPU, but for their purpose they absolutely shred though large data. This has given rise to GpGPU Computing, or General Purpose Graphics Processing Unit Computing, where in the GPU is used for things other than graphics, like accelerating database searchers or training AI models.

Okay, so, saying thousands of cores is sort of a lie. It really depends on how you define a ‘core’. It’s really more fair to compare cores of a CPU to Compute Units (CUs) of a GPU. Gentle Introduction to GPUs inner workings (vkSegfault) goes into this quite well, but assumes more technical background than that title might imply. The ‘Parallel Architectures’ page from Nvidia’s ‘The Graphics Codex’ is a good resource too.

As a brief note, historically graphics cards served primarily to actually draw to the screen, with some only having a fixed number of characters they could draw for rendering a text interface and others having a quite limited color palette that dictated how final images would look.

Today, there are three primary manufactures of GPUs: Nvidia, AMD, and Intel.

The largest player in the space, Nvidia, makes cards targeted primarily to gamers in their GTX and RTX lineup, and has cards meant for professional/compute tasks in their Tesla and Quadro lines. While the two lines are very similar technically, they vary mostly in drivers and compute bit depth, with the professional cards providing the ability to do higher resolution floating point calculations easier. This is primarily done for market segmentation, though- to prevent professional from buying the much cheaper (albeit still far too expensive) ‘gaming’ cards. All of Nvidia’s cards support CUDA, a programming framework that makes it easier to take advantage of Nvidia’s cards for GpGPU purposes.

AMD is currently offering little competition to Nvidia in the high end; however, their more midrange cards have found great success, as they perform plenty well for the majority of games and compute work loads at what is often a fraction of the cost. Of note, AMD cards do not support CUDA, though they do support a variety of open standards that serve the same purpose. This is still an issue, though, as many programs that can take advantage of GpGPU acceleration depend on CUDA and therefor require an Nvidia card. Nvidia has frequently been quite hostile to the open source community, and their drivers significantly lag behind in quality and performance compared to AMD’s for Linux.

Also of note, AMD makes many ‘APU’s or Accelerated Processing Units, which is just branding for their take on graphics integrated into the CPU. However, AMD’s integrated graphics, at least at the moment, far out do Intel’s offerings. Intel, at the moment, only offers integrated graphics that are less than stellar performers. Despite this, laptops with Intel Integrated Graphics are very common due to their low power usage. Intel’s Integrated Graphics have very good drive support, though, both on Linux and Windows.

As of the time of writing, Intel is starting to send prototype graphics cards to vendors in a bid to break out of the integrated graphics only space.

Moving into the actual hardware itself, let’s look at three graphics units, starting with Intel Integrated.

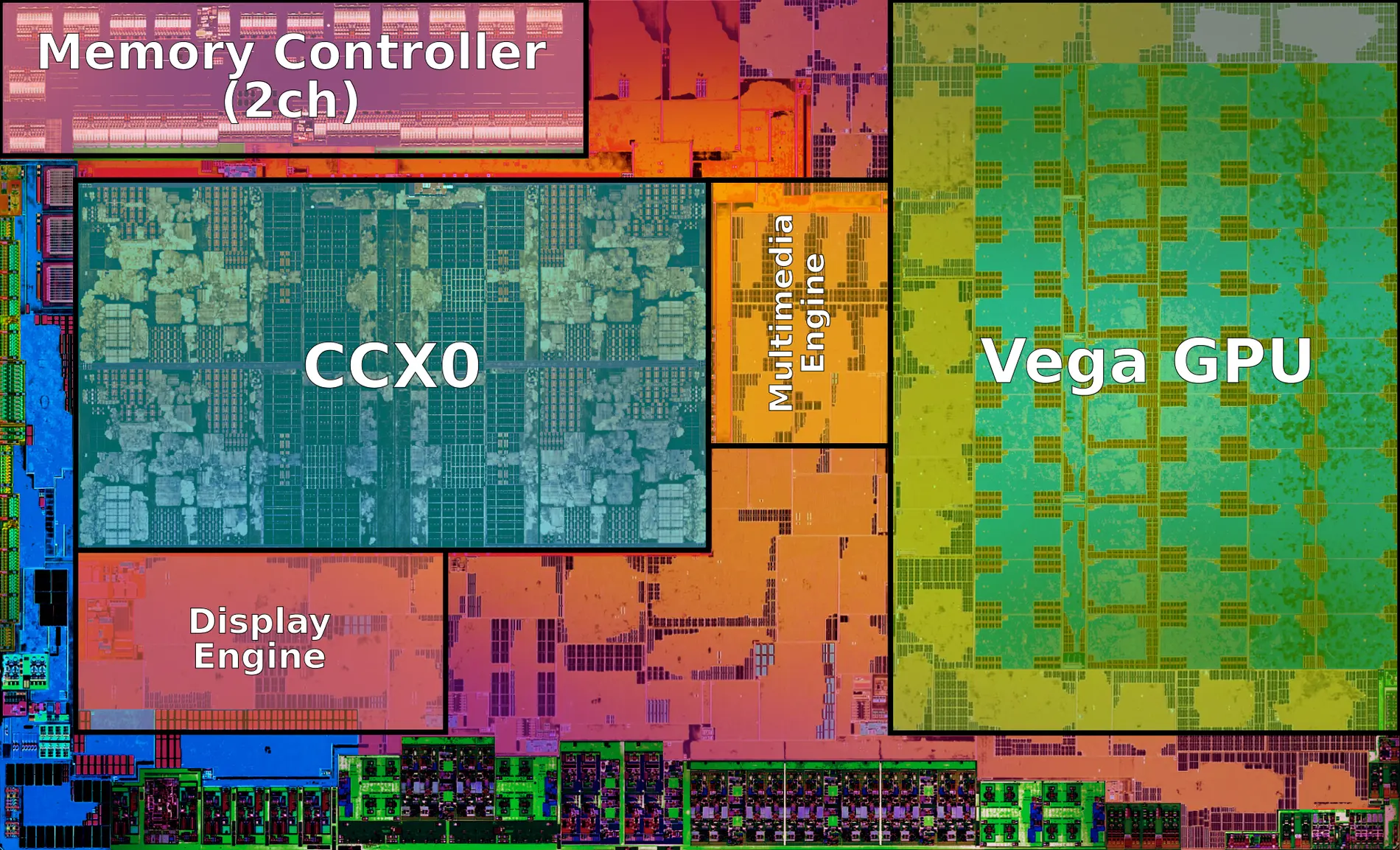

Both Intel and AMD offer integrated graphics of various capability that usually pair reasonably well with the CPU they share the die with. Below is an image of the inner workings of a ryzen CPU with integrated graphics, showing the actual CPU cores (I believe this is a 4 core eight thread system?) in CCX0, the memory controller, and the very large Vega series GPU on the right. This looks to be a Vega11 GPU as you can count the 11 stacks of Compute Units in the GPU section. Of note, if you get a CPU with integrated graphics and don’t actually use it because you’re getting a separate, more powerful card, then you’re effectively paying for a large amount of hardware you’re not using. As you can see below, if the GPU was not there, there would be a lot more room to add more CPU cores or other features to the CPU to make it more powerful. Unfortunately, due to market segmentation even if the actual cost to add these extra cores would be the same or less as the iGPU’s cost, a CPU of the equivalent size would likely be much more expensive.

Finally, it should be noted the iGPUs share system memory for graphics memory, which is actually one of their most limiting factors- as system memory (RAM) is optimized for a different kind of access pattern, it is not nearly as fast as GDDR or HMB2, both of which are memory technologies that have been optimized for use with graphics devices.

Moving on to graphics cards, looking above at the stacks of graphics cards above, you’ll probably notice that a graphics card is basically just a full separate motherboard and processor on a card. Really, this is pretty accurate, as there is a separate compute device (the GPU), ram (GDDR or HBM), and io (fan control, etc.) on the board. Of course, the Graphics card can’t really be used as a full separate computer, but thinking about it as such isn’t entirely wrong either. In fact, graphics cards really harken back to much older systems, where it was common to add a math coprocessor chip alongside the CPU to make some mathematical operations faster.

Further reading on GPU hardware:

“World’s Simplest TTL VGA circuit?” - George Foot on Hackaday

Hardware Acceleration #

Cerebras Wafer Scale Engine: Why we need big chips for Deep Learning

Hardware Accelerated Decode #

[TODO]

https://utcc.utoronto.ca/~cks/space/blog/web/Firefox80VideoAccelConfusion

A trip through the Graphics Pipeline 2011: Index

A note I have no better place to put: On Windows, if you press Win+Ctrl+Shift+B you can force your GPU driver to reset. This can get you out of some (but not all) lock ups. Handy to keep in mind.