Chapter 3½ - Architectures #

Instruction Set Architectures #

Today, there are two main computer architectures you’ll use x86_64 and ARM. You’ve probably heard this in passing, but you may not know what they are. These are Instruction Set Architectures (ISA), and they define the list of instructions your computer can understand and the basics about how those instructions are laid out.

Let’s say we have a fictional computer, really old, that’s only 8-bit (most modern systems are 32 or 64bit) this would mean we get eight 1’s and 0’s to define our instruction. We might decide to have the first 4 bits hold the Opcode (short for Operation Code) We might decide that any instruction starting with 0000 is a store, 0001 a move, 0010 a jump, 0011 an add, and so on. Then, we might say the other four bits should represent registers, that is, locations of other numbers. So we might have 00110110 where the 0011 means add, and the next two bits, 01, mean registers 1 and the next two bits, 10, mean register 2. For this, we’d probably have to assume the result gets stored in one of these registers, so it might be that 00110110 means add the numbers in register 1 and register 2 and store the result back into register 1.

The next thing you should know is that there are two kinds of instruction sets: CISC and RISC. CISC is Complex Instruction Set Computer, and RISC is Reduced Instruction Set Computer.

The names are pretty self-explanatory. While CISC may have a ton of specialty instructions for doing bigger tasks in one instruction (for example, PSHUFB: Packed Shuffle Bytes or MPSADBW: Compute Multiple Packed Sums of Absolute Difference, if you’d like to have your brain hurt for a moment). This is compared to RISC, where there’s usually dramatically less instructions. A bit counterintuitively, RISC has generally been found to be a bit faster (or at least more efficient, and in many system you’re limited by how much heat you can get rid of - so, it’s faster by way of being more efficient), because even though the individual instructions can’t do as much, they can be pipelined (a topic we’ll go over later) much more easily.

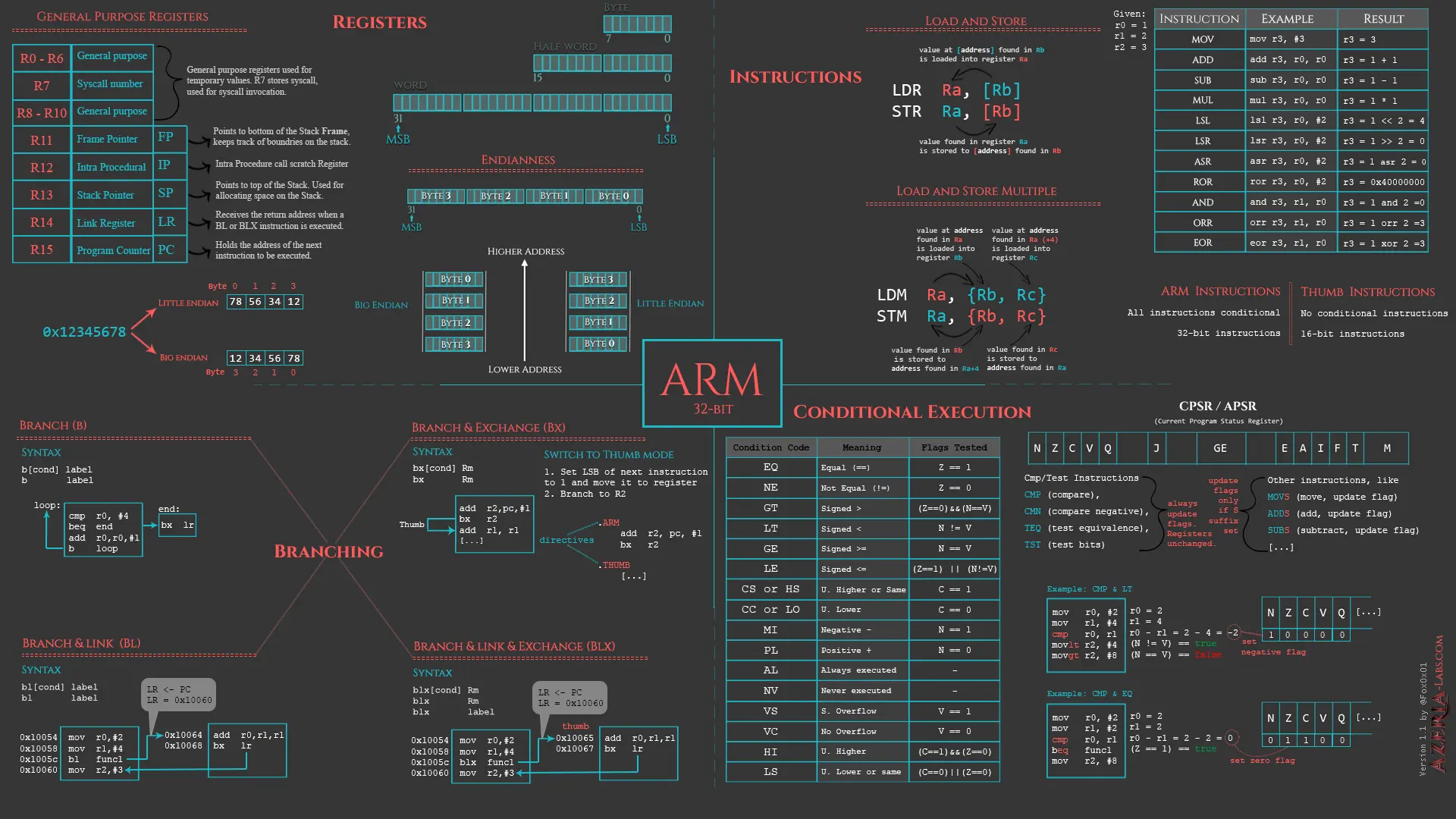

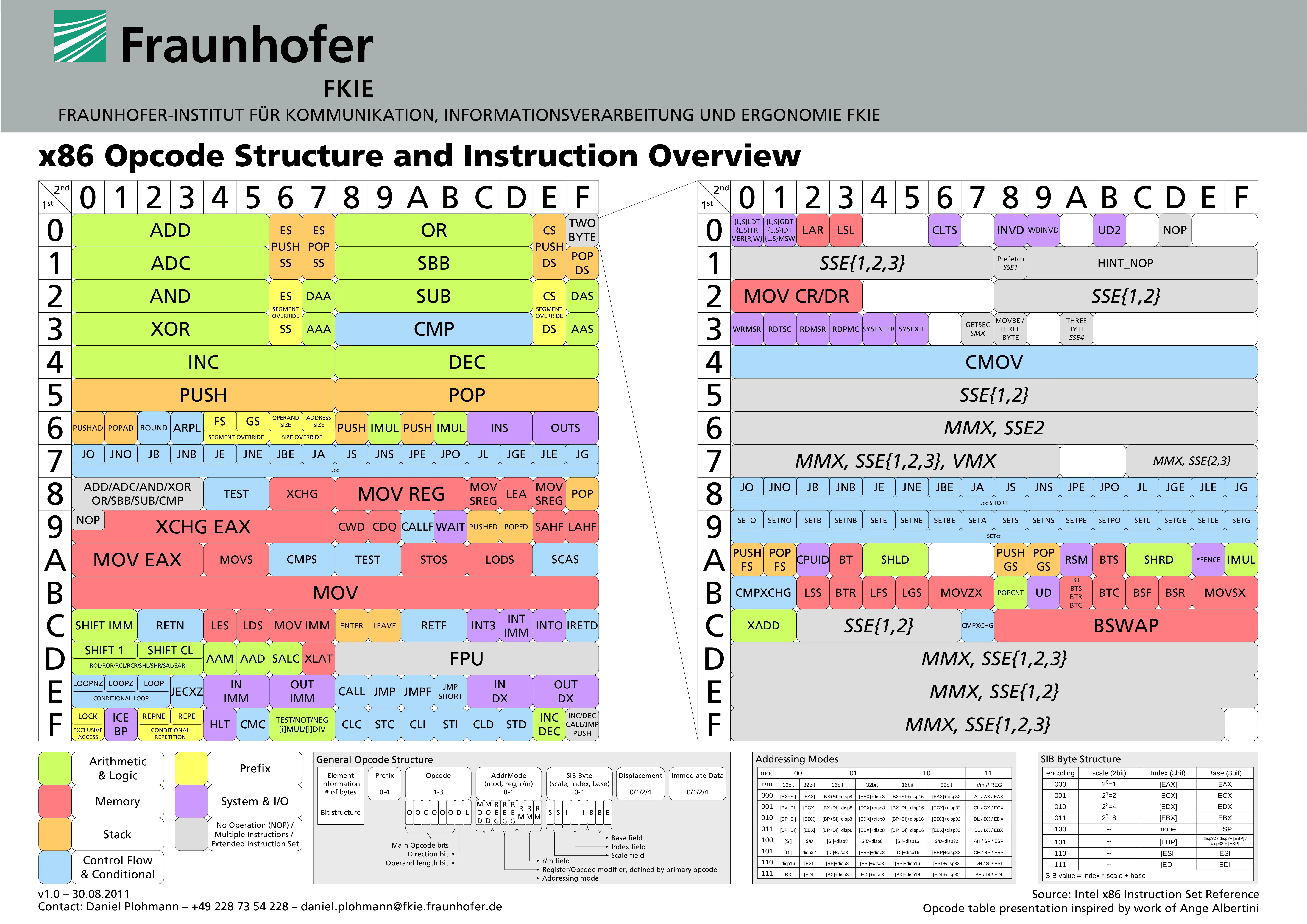

Just for comparison, check out this ARM assembly code cheat sheet from Azeria Labs vs this x86 opcode cheat sheet:

It’s also a bit stunning just how rarely a lot of x86_64 instructions are even used:

@pepijndevos re: "Does a compiler use all x86 instructions?" 942 unique instructions, most common are mov, lea, call, int, je, jmp, cmp. 25 instructions appear only once. pic.twitter.com/IJtI4Y5rJD

— Vega Deftwing (@Vega_DW) May 12, 2021

Part of what makes this so complicated is the variety of instructions available even for what sounds like a standard set. Not all processors with the same ISA actually support the same instructions. Both x86_64 and ARM have gotten a lot of instruction set extensions, see Wikipedia’s x86 instruction listings just to get an idea of this. You may even see some of these mentioned in conversation about what CPU to buy, for example, at the time of writing only a subset of modern desktop processors support AVX-512, a 512-bit instruction (yes, that’s a thing, even on 64bit systems) that should make some workloads faster.

There’s a lot more to computer architecture than this. I only touched on the difference in instruction sets, not how two processors that both implement the same instruction set may vary wildly in actual implementation or how there are different schools of thought when it comes to having memory be separate or combined for data and instructions. We’ll come back to that later, though, in Chapter 29: Let’s Make our own CPU.

I do want to leave you with something to ponder though- here’s a list of ISAs supported by Radare2, a reverse engineering toolkit:

Architectures

i386, x86-64, ARM, MIPS, PowerPC, SPARC, RISC-V, SH, m68k, m680x, AVR, XAP, System Z, XCore, CR16, HPPA, ARC, Blackfin, Z80, H8/300, V810, V850, CRIS, XAP, PIC, LM32, 8051, 6502, i4004, i8080, Propeller, Tricore, CHIP-8, LH5801, T8200, GameBoy, SNES, SPC700, MSP430, Xtensa, NIOS II, Java, Dalvik, WebAssembly, MSIL, EBC, TMS320 (c54x, c55x, c55+, c66), Hexagon, Brainfuck, Malbolge, whitespace, DCPU16, LANAI, MCORE, mcs96, RSP, SuperH-4, VAX.

From the README.md file at https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

Operating Systems and SysCalls #

For lack of a better place to put it, it’s worth pointing out that just because a program is made up of the correct instructions for a given processor, doesn’t necessarily mean it will run on that architecture without some surrounding context to make it work correctly. The most obvious thing that mucks things up in this regard is the Operating System being used. Obviously, a program written for Windows and a program written for Linux (usually) won’t run on the other without some sort of compatibility layer like Wine or WSL. This is mostly because pretty much any non-trivial program will need to use system calls (often abbreviated to ‘syscall’) which is, very basically, just the OS specifying that any request for hardware access (say, opening a file, writing data to disk, getting network access, etc.). This list of system calls and how they’re requested will vary between operating systems. So now we have a mix of Instruction Set Architectures (with a mix of extensions) and a mix of operating systems, so that must be the full picture, right?

Ha. No. But before I go further, I do want to point out that while I mentioned Windows and Linux, obviously there’s a lot more than this. There’s macOS, Android, iOS, and a huge variety of smaller projects like TempleOS and Haiku.

Executable File Formats #

So, what else contributes to the incompatibilities? Well, one major one is the large variety of executable formats. Some of these formats are effectively just a bunch of instructions for their respective architecture with a little bit of information tacked on to point to shared system libraries, others (like java jars) are executable formats that depend on using a virtual machine to try to work around the incompatibility issues between ISAs and Operating Systems.

File Formats

ELF, Mach-O, Fatmach-O, PE, PE+, MZ, COFF, OMF, TE, XBE, BIOS/UEFI, Dyldcache, DEX, ART, CGC, Java class, Android boot image, Plan9 executable, ZIMG, MBN/SBL bootloader, ELF coredump, MDMP (Windows minidump), WASM (WebAssembly binary), Commodore VICE emulator, QNX, Game Boy (Advance), Nintendo DS ROMs and Nintendo 3DS FIRMs, various filesystems.

From the README.md file at https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

[TODO] note on hackintoshes

https://manybutfinite.com/post/how-computers-boot-up/

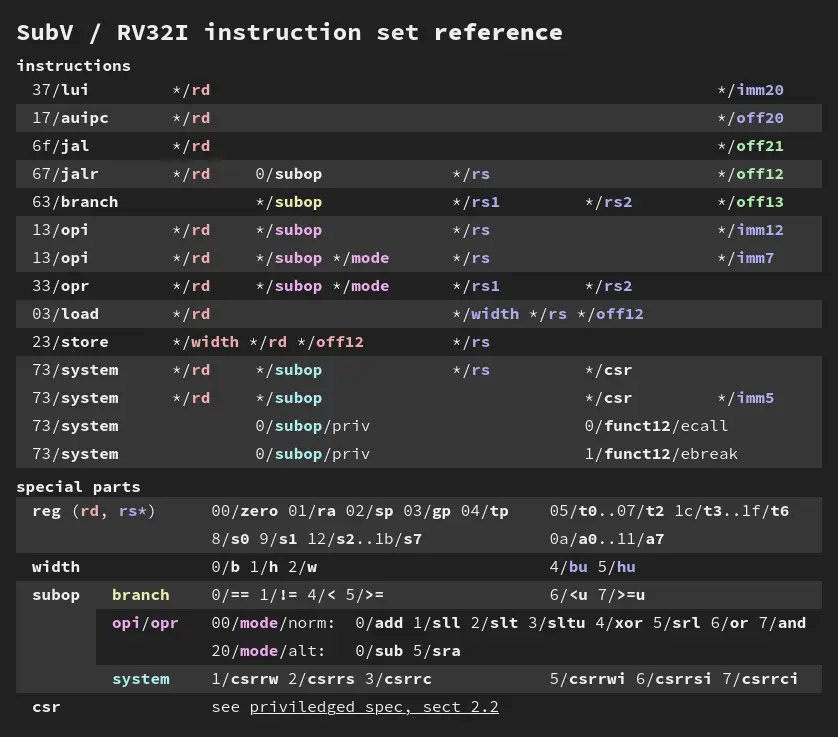

In case you need it, here’s a SubV/RiscV ISA ref sheet: